… Reassessing Krishnamurti in Later Life”

by Ricardo Morín

July 2025

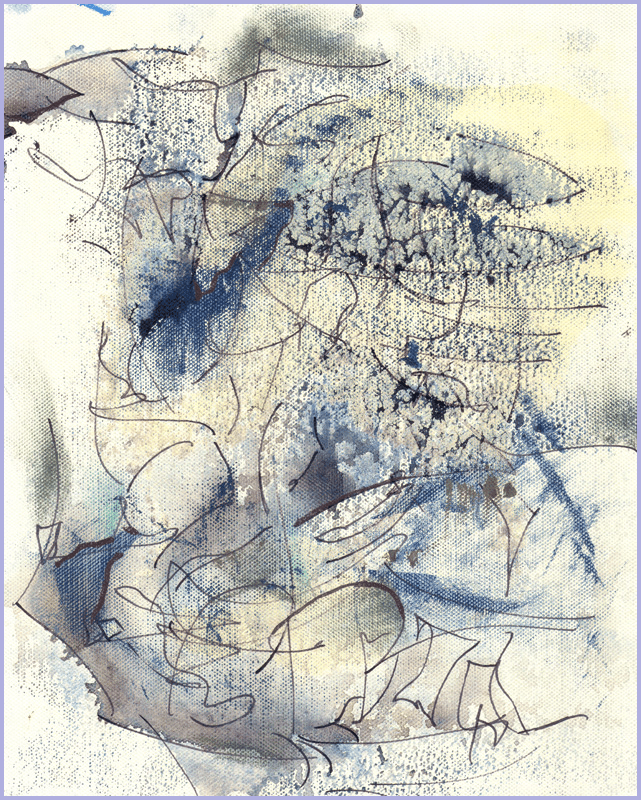

Infinity 6

12” x 15”

Oil and ink on linen

2005

*

Abstract

This reflective essay reconsiders the thought of Jiddu Krishnamurti through the lens of aging and evolving philosophical expectations. While Krishnamurti’s teachings once offered inspiration and a path toward inner freedom, they now appear to dissolve into rhetorical mysticism and incoherence. The essay critiques his rejection of “intellectual understanding” and analyzes the contradictions inherent in his style of spiritual discourse. It argues for the necessity of rational clarity, especially in later stages of life when discernment becomes more valuable than inspiration alone. This shift is presented not as a betrayal of earlier insight, but as its maturation.

“Listening Beyond the Trance: Reassessing Krishnamurti in Later Life”

In my forties and fifties, I found great inspiration in the thought of Jiddu Krishnamurti. His emphasis on freedom from authority, his critique of systems, and his call to radical self-awareness spoke directly to a part of me that sought liberation from inherited dogmas and psychological conditioning. He offered, or seemed to offer, a clarity beyond tradition—a voice that felt both universal and personal.

But now, in my seventies, I find myself rereading his words with a different ear. What once felt revelatory now strikes me as elusive, at times incoherent. A recent passage shared by the Krishnamurti Foundation, drawn from a 1962 public talk in New Delhi, crystallized this shift for me:

“There is no such thing as intellectual understanding; you really only mean that you hear the words, and the words have some meaning similar to your own, and that similarity you call understanding, intellectual agreement. There is no such thing as intellectual agreement – either you understand or do not understand. To understand deeply, with all your being, you have to listen”.

This line of thinking—expressed in varied forms across his oeuvre—once felt like an invitation to presence. Now, I hear it differently: as a kind of rhetorical mysticism that dismisses the very faculties we depend on to make meaning. The claim that “there is no such thing as intellectual understanding” is not merely provocative; it is self-undermining. If words cannot convey meaning through reason, then why speak? Why write? Why gather an audience at all?

Krishnamurti’s sharp dichotomy between “intellectual” and “real” understanding collapses under scrutiny. Intellectual reflection is not merely passive recognition of familiar ideas. It is the groundwork of discernment—of logic, dialogue, and ethical clarity. To discard it is to unravel the very possibility of communication. What he seems to offer instead is a kind of pure, undefinable receptivity—“listening with all your being”—a state left vague, idealized, and unexamined.

This tendency is not unique to Krishnamurti. It is a feature of a broader strand of Indian and global spiritual discourse that wraps itself in the aura of wisdom while resisting the discipline of logic. It blurs the line between paradox and nonsense, invoking transcendence but offering no clear ground. What results is not insight but opacity.

None of this erases what Krishnamurti once offered me. His call to question, to observe without prejudice, helped me unlearn many habits of thought. But inspiration and clarity are not the same. The mind that once needed liberation may later need precision.

We change. What moves us at one stage of life may lose its grip as our questions evolve. That does not make earlier experiences false—it simply means that our standards grow. In listening now, I want something more than the echo of profundity. I want coherence. I want meaning that can stand up to thought.

Krishnamurti taught me to listen. That lesson remains. But now, I listen not only with receptivity—but with reason, with discernment, and with the quiet courage to call abstraction what it is.

*

Annotated Bibliography:

- Krishnamurti, Jiddu: The First and Last Freedom. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1954. (A collection of early talks that established Krishnamurti’s core ideas; includes his foundational argument against psychological authority and tradition.)

- ———: Commentaries on Living, First Series. Madras: Krishnamurti Foundation India, 1956. (Brief philosophical dialogues drawn from real encounters; written in prose that oscillates between clarity and metaphysical opacity.)

- ———: The Awakening of Intelligence. New York: Harper & Row, 1973. (A comprehensive transcript of public discussions and interviews where Krishnamurti expands his rejection of intellectual systems and explores “pure observation.”)

- ———: The Wholeness of Life. London: Victor Gollancz, 1978. (A late-career synthesis that juxtaposes technological anxiety with inward freedom; his critique of organized thought becomes more abstract here.)

- ———: Krishnamurti to Himself: His Last Journal. San Francisco: Harper San Francisco, 1987. (Dictated reflections shortly before his death; his rejection of analysis deepens and borders on mysticism, with lyrical but imprecise language.)

- ———: The Ending of Time: Where Philosophy and Physics Meet. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1985. (Conversations with physicist David Bohm; illustrative of Krishnamurti’s dismissal of conventional logic even when in dialogue with a scientist.)

- Murti, T. R. V.: The Central Philosophy of Buddhism: A Study of the Mādhyamika System. London: George Allen & Unwin, 1955. (A key work in Buddhist philosophical reasoning; useful contrast to Krishnamurti in that it pursues dialectical rigor rather than mystical generality.)

- Ganeri, Jonardon: Philosophy in Classical India: The Proper Work of Reason. London: Routledge, 2001. (Challenges the stereotype that Indian thought is mystical or anti-rational; highlights traditions that value analysis and inference over insight alone.)

- Nussbaum, Martha C.: Cultivating Humanity: A Classical Defense of Reform in Liberal Education Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997. (Advocates for clarity, rational argument, and intellectual pluralism; offers a counterpoint to Krishnamurti’s anti-intellectualism.)

- McGinn, Colin: The Making of a Philosopher: My Journey Through Twentieth-Century Philosophy. New York: HarperCollins, 2002. (A memoir that models the philosophical maturation process; echoes the author’s own shift from inspiration to the pursuit of clarity.)

*

Tags: aging, authority, coherence, critical thinking, doubt, Krishnamurti, philosophy, spirituality

PLease leave a Reply