… Rethinking Identity and Belonging in Civic Life”

By Ricardo Morin

July 2025

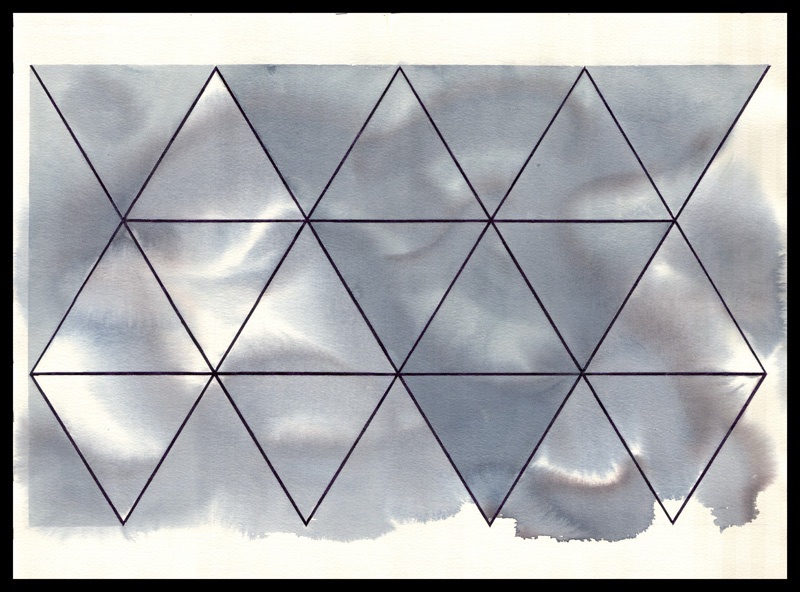

Silence III

22’ x 30”

Watercolor, graphite, gesso, acrylic on paper

2010

Abstract

This essay explores the moral and civic tensions between identity and democratic belonging. While the affirmation of cultural, ethnic, or political identity can offer dignity and solidarity, it can also harden into exclusionary boundaries. The essay argues that liberal democracies must find ways to acknowledge difference without allowing it to erode shared commitments to equal rights, mutual recognition, and the rule of law. Drawing on historical reflection and philosophical insight, it calls for a civic imagination that resists reductionism and makes space for the full complexity of human life.

*

“Lines That Divide: Rethinking Identity and Belonging in Civic Life”

The idea of a people signifies more than shared humanity—it evokes a sense of belonging, shaped by culture, memory, and mutual recognition. At its best, it names the bonds that tie individuals to communities, traditions, and aspirations larger than themselves. Yet when the phrase my people becomes a marker of separation or proprietary ownership over culture, suffering, or truth, it risks reinforcing the very divisions that our civic and legal frameworks aim to overcome. What begins as a declaration of identity can easily become a posture of exclusion. We hear it in moments of pain, pride, or fear: “You wouldn’t understand—you’re not one of us.” Sometimes that is true. But when the language of belonging hardens into a refusal to listen or an excuse not to care, it stops being a refuge and becomes a wall.

Throughout history, group identities—whether national, racial, religious, or political—have served both as sources of solidarity and as instruments of division. While identity offers a means to reclaim dignity and assert visibility in the face of marginalization, it also contains the seeds of separation. The line between affirmation and alienation is perilously thin. The same identity that uplifts a community can harden into a boundary that isolates others. It is a double-edged sword: capable of healing or harming, depending on how it is wielded.

The modern democratic project rests on a delicate balance: it must recognize difference while upholding equality. Liberal democracies are premised on the idea that all individuals, regardless of group affiliation, possess equal rights under the law. It’s a principle taught in early childhood, often before it’s fully understood: the sense that rules should be fair, that being left out or judged before being known feels wrong. That early moral intuition is echoed in constitutional promises, which exist not just to reflect majorities but to protect the dignity of each person, especially when they are in the minority—of belief, background, or circumstance.

The goal is not to erase identity, but to prevent it from becoming the sole axis along which rights, value, or participation are measured. When identity becomes the primary currency of belonging, we risk turning citizenship into a competition of grievances, where recognition is awarded only at the expense of others.

This problem is not abstract. We see it daily in public discourse, where appeals to identity often overshadow appeals to principle. The phrase my people can be used to claim historical injury, moral superiority, or cultural authority—but it can also suggest exclusion, as if others are not part of that moral circle. The danger lies in what is left unsaid: who is not included in my people? Who becomes them?

Such binaries—us versus them—flatten the complexity of human relationships and obscure our mutual dependence. In truth, no community exists in isolation. Our economies, institutions, and ecosystems are inextricably linked. The law is designed to reflect that interdependence by granting rights universally, not tribally. Yet when identity becomes the filter through which justice is demanded or denied, the rule of law suffers. Justice ceases to be blind and becomes instead a servant of factional interests.

This does not mean we should abandon the language of identity. Cultural and historical specificity matter. Erasing them in the name of unity risks another form of injustice: the silencing of lived experiences. The solution is not to reject identity, but to contextualize it—to understand it as one part of a broader human condition, rather than the totality of a person’s worth or moral standing.

To move forward, we must ask a hard question: Can we acknowledge identity without allowing it to calcify into division? Can we affirm cultural or historical differences while building institutions and relationships that are capacious enough to include those unlike ourselves?

Doing so requires more than tolerance. It demands a civic imagination—one that envisions solidarity not as uniformity, but as the commitment to coexist with dignity across lines of difference. It means seeing others not primarily as representatives of a group, but as individuals with rights, needs, and aspirations equal to our own. It means remembering that no one can be fully known by a single trait, history, or belonging—not even ourselves. We each carry contradictions: tenderness alongside prejudice, loyalty tangled with resentment, the need to be seen and the fear of being exposed. To honor our shared humanity is to make space for that complexity—not to excuse harm, but to understand that moral life begins not with certainty, but with humility.

Ultimately, the challenge of our time is not merely to recognize difference, but to live with it constructively. The real test of a pluralistic society is not how loudly it proclaims diversity, but how equitably it distributes belonging. To succeed, we must shift from my people to our people—not as an erasure of identity, but as a deeper, shared commitment to the fragile experiment of coexistence.

*

Annotated Bibliography

Appiah, Kwame Anthony: The Lies That Bind: Rethinking Identity. New York: Liveright, 2018. (Explores how identities such as race, creed, and nation are constructed, sustained, and misused—calling for a more flexible, cosmopolitan ethics.)

Arendt, Hannah: The Human Condition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1958. (Analyzes the nature of political life and plurality, grounding civic belonging in the shared space of action and speech rather than fixed identities.)

Benhabib, Seyla: The Claims of Culture: Equality and Diversity in the Global Era. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002. (Defends universal human rights while acknowledging the legitimacy of cultural claims—proposing a model of democratic iterations.)

Fukuyama, Francis: Identity: The Demand for Dignity and the Politics of Resentment. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2018. (Traces the rise of identity politics globally and its impact on democratic institutions, arguing for a re-centering of shared civic values.)

Glazer, Nathan, and Daniel P. Moynihan: Beyond the Melting Pot: The Negroes, Puerto Ricans, Jews, Italians and Irish of New York City. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1963. (Classic sociological study showing how ethnic identities persist across generations and shape urban belonging in complex, often contradictory ways.)

Hooks, Bell: Yearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics. Boston: South End Press, 1990. (Critiques exclusionary forms of identity politics and calls for forms of solidarity that cross boundaries of race, gender, and class.)

Ignatieff, Michael: Blood and Belonging: Journeys into the New Nationalism. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1994. (Personal and political reflections on nationalism in the post–Cold War era, warning of the moral danger in defining belonging through ancestry.)

Rawls, John: Political Liberalism. New York: Columbia University Press, 1993. (Presents a theory of justice grounded in overlapping consensus rather than shared identity, advocating for stability in a pluralist society.)

Taylor, Charles: Multiculturalism: Examining the Politics of Recognition. Edited by Amy Gutmann. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994. (Argues that recognition of cultural identity is vital to individual dignity, but must be balanced within a just liberal framework.)

Wiesel, Elie: Nobel Peace Prize Lecture. Oslo: Nobel Foundation, 1986. (A deeply moral reflection on human solidarity, memory, and the responsibility to resist indifference—invoking identity without exclusion.)

Tags: Belonging, civic life, culture, democracy, difference, exclusion, Identity, solidarity

PLease leave a Reply