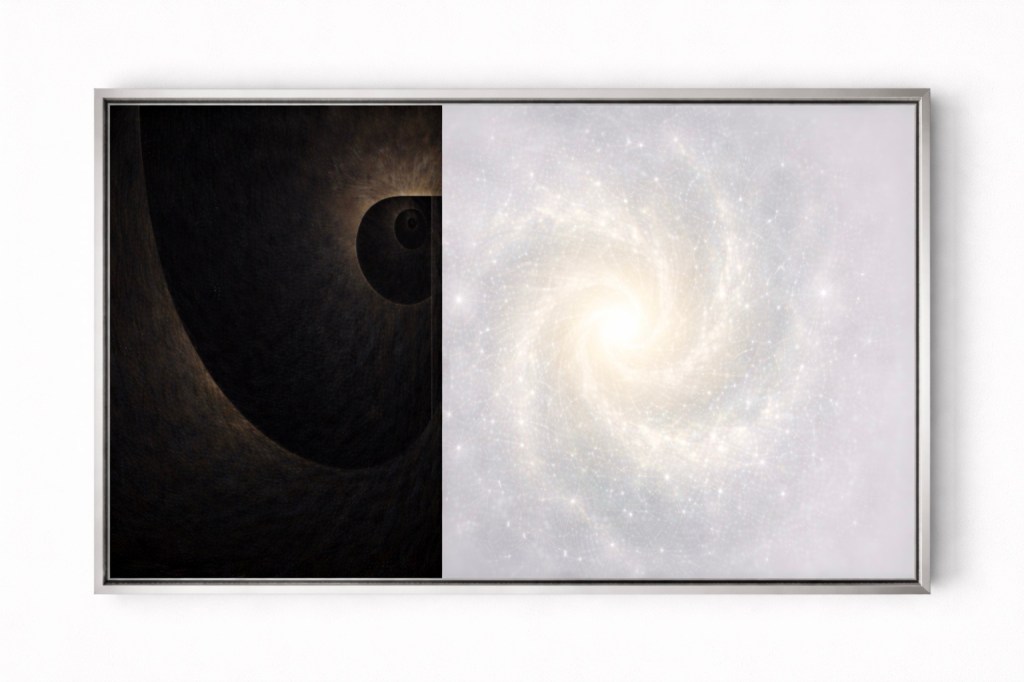

What It Is; What Is Not

CGI

2026

Ricardo F. Morín

January 5, 2026

Oakland Park, Fl.

Wannabe Axiom IV

Resilience is often introduced as a descriptive term. It names a capacity observed under pressure, a tendency to endure when conditions cannot immediately be altered. In this sense, resilience appears neutral, even commendable. It signals survival where collapse was possible, continuity where interruption was expected.

Over time, however, resilience ceases to be merely observed and begins to be praised. What was once noted becomes celebrated. Endurance is elevated into virtue, and the ability to persist under strain is held up as evidence of strength. In this shift, attention subtly moves away from the conditions that necessitated endurance in the first place.

Once resilience is praised, it becomes expectable. The language of admiration gives way to the language of obligation. What some managed to do under duress is gradually treated as what all should do. Endurance stops being exceptional and becomes normative. The capacity to withstand replaces the question of why endurance is required.

At this point, resilience performs a quiet inversion. Conditions remain intact, while responsibility migrates toward those exposed to them. Structures are left unexamined as individuals are encouraged to adapt. Adjustment is relocated from systems to subjects. What cannot be repaired is to be endured.

This inversion carries a temporal dimension. Resilience is framed as forward-looking strength, a promise that persistence will eventually be rewarded. Harm is deferred rather than addressed. Recovery is invoked in place of repair, and time is asked to absorb what policy or structure does not resolve.

The ethical weight of this shift is unevenly distributed. Those with the least capacity to alter their circumstances are most frequently called upon to be resilient. Those with the greatest power to change conditions are least exposed to the demands of adaptation. Resilience, though praised as universal, is imposed asymmetrically.

As resilience becomes an expectation, dissent softens rather than disappears. Complaint is not forbidden, but it is recoded. Questioning conditions is treated as impatience. Refusal to endure is framed as deficiency. Endurance itself becomes a measure of maturity, and silence is mistaken for consent.

What resilience is, then, is a capacity to endure conditions not of one’s making. It is a descriptive fact of human behavior under pressure. It names survival where alternatives are limited.

What resilience is not is an ethic. It is not a justification for harm, nor evidence that conditions are acceptable. The ability to endure does not confer legitimacy on what is endured.