*

Ricardo Morin, August 25, 2025

*

From the Alice Maguire Museum at Saint Joseph’s University in Lower Merion Township, we moved among its holdings. The stained-glass windows were luminous and unsettling: John the Baptist with the Sacred Lamb, a Madonna and Child, a Pietà, a Return of the Prodigal Son. Once embedded in the walls of churches, they now stood uprooted from their sacred setting, their narratives suspended. Freed from liturgical purpose, they spoke instead through pure rhythm—cobalt and ruby, emerald and gold—colors as commanding as Veronese or Tintoretto, structures as fractured and daring as Picasso or Soutine. In their displacement, their dramatic effect delighted both the eye and the mind in their own right.

Another room revealed the Heavenly and Earthly Trinities of colonial Peru, the anonymous painters of Bolivia, and the Hispano-Philippine baroque sculptors: nameless hands shaping images to satisfy imperial taste. Their works obeyed the conventions of European devotion, yet beneath the surface ran other currents. A palette tinged with local sensibility, a face, an ornament not found in Seville or Rome—small gestures of persistence within the language of conquest. The absence of names testified to a system where identities were erased, but expression still found a way through brushstroke and chisel.

And then, standing apart, an eighteenth-century Mexican vargueño. A desk suited to a monarch’s scribe, its fall-front concealing drawers and secrets, its ironwork and gilding gleaming like a promise of empire. Imported as form but transformed by New World artisanship, it became a hybrid of Spanish order and Mexican material richness. Not merely a piece of furniture, but a portable stage of authority that bears within it the weight of rule and the quiet labor of those who made it.

Leaving the museum, we stepped into the arboretum. The shift was immediate. The bright lawn spread before us, lilacs already past bloom, the air holding the mixture of late summer and the first breath of fall. In the distance I saw David at the forest’s edge, as he was pointing to the broken silhouettes of trees—some uprooted, others scarred by the saw. It was difficult to tell whether their loss came from the slow processes of age and decay, or from the harsher pressures of climate change. The sight of those old, magnificent trunks reduced to stumps and exposed roots carried the weight of both inevitability and warning. I whistled to catch up with him, the sound bridging the distance between us and the wounded landscape.

The grounds themselves bore another absence. This land, once owned by Dr. Albert Barnes, preserves his legacy in plaques and praise, yet his presence is no longer here. Like the uprooted trees, the founder has been torn from the landscape—remembered in word but not in flesh. His vision endures in the collections and in the cultivated order of the arboretum, but the man himself is gone, leaving only traces: the architecture, the gardens, the echoes of intention.

Even the memory of Barnes is shadowed by discord. His decision to raise a ten-foot wall, blocking the view of his neighbors, was more than an act of stubborn privacy—it became a testament to the conflict between ways of seeing, both in art and in life. Just as his collection challenged the conventions of museums, so too his wall imposed his vision upon the landscape, as his efforts uprooted not only visibility but also harmony with those around him.

The uprooting of the collection has been chronicled not only in print but on film. Don Argott’s The Art of the Steal (2009) captures the drawn-out conflict between Barnes’s will, his Merion neighbors, and the powerful interests that sought the collection’s relocation: the film portrays the move as both civic triumph and cultural betrayal. More recently, Donor Intent Gone Wrong (Philanthropy Roundtable, 2022) framed the dispute as a cautionary tale about institutions overriding individual vision. Together, these accounts testify that the collection’s dislocation was never merely architectural: it was an uprooting of purpose as much as of place.

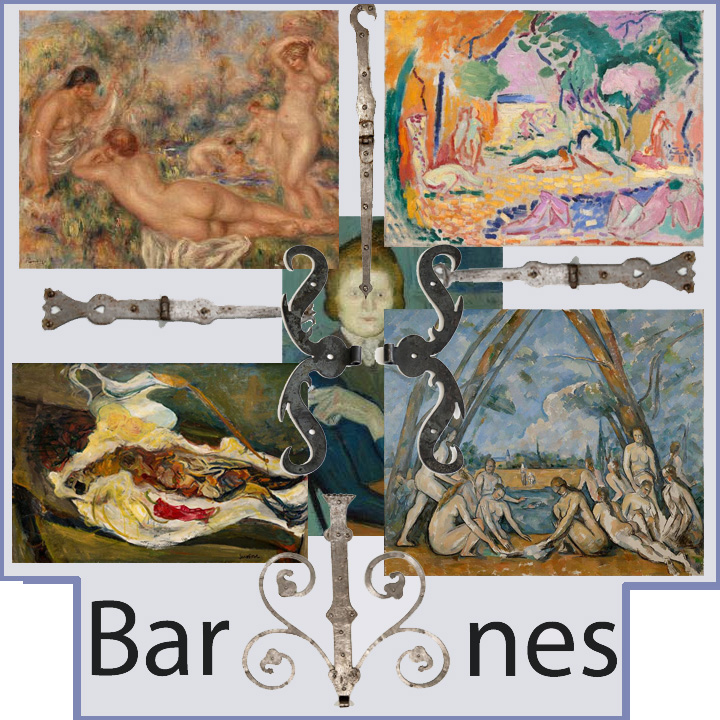

A collection of modern art—though invaluable and managed by the Pew Foundation at an estimated value of sixty-seven billion dollars—does not carry the same intensity as Barnes’s once-private holdings. A new museum dedicated to his collection now stands in its own building on Philadelphia’s museum row along the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, beginning with the Franklin Institute of Science and ending with the Barnes Museum eastward. What was once an idiosyncratic, fiercely personal vision now exists under the stewardship of curators who inevitably impose a different order. Where Barnes once arranged paintings shoulder to shoulder—Renoirs beside African masks, Cézannes and Matisses above medieval ironwork—the new installation gravitates in misalignment with the grammar of conventional museums, categorized by school, chronology, or theme, yet still incongruous with the artifacts mixed among them. The intimacy of a domestic space has been exchanged for the grandeur of a public institution, and with it the friction between his vision and institutional norms becomes palpable. Visitors now move through broad galleries instead of the dense, almost confrontational ensembles he once defended.

What endures, however, is the sense of the collection as Barnes’s own installation, authored in the spirit of both philosophy and biography. His juxtapositions were deliberate compositions: Renoirs beside iron hinges, Cézannes above ladles, African masks flanking Impressionist portraits. Around them clustered the objects he loved to collect—door latches, lock plates, wagon parts, Pennsylvania German chests, Navajo textiles, and hundreds of wrought-iron hinges and utensils. These were never curiosities: for Barnes, each hinge, each utensil, each mask was an equal actor in the ensemble, sharpening the perception of form and rhythm in the canvases above. Influenced by his friend John Dewey, Barnes believed that art should be experienced democratically, where the humble and the exalted shared the same plane of visual inquiry.

The paradox is that the collection has never been more visible, yet perhaps never less itself. In its transformation from private sanctuary to public museum, from the defiant eccentricity of a man’s will to the polished authority of the Parkway, it has acquired a new layer of politics. Praise for its accessibility is constant, but so too is the quiet sense that something has been uprooted: the personal order replaced by the institutional, the disruptive vision softened by curatorial compromise. And yet, despite these shifts, the collection still resists full assimilation. The paintings, the juxtapositions, the sheer density of presence retain their charge, as they remind us of the one man who dared to see differently—even when it set him against his neighbors, his city, and the established conventions of art.

*

Annotated Bibliography

- Argott, Don, dir. The Art of the Steal: The Untold Story of the Barnes Collection. 2009. Film. Maj Productions and 9.14 Pictures.— A riveting documentary tracing the decades-long legal and civic battle over the relocation of the Barnes Foundation from Merion to Philadelphia. It highlights neighborhood opposition, donor-intent controversies, and the institutional forces that uprooted Barnes’s educational vision—ideal for understanding how physical displacement mirrors conceptual disruption.

- Barnes Foundation. The Barnes Foundation: Masterworks. New York: Skira Rizzoli, 2012.— A richly illustrated volume presenting the paintings, sculptures, and ensembles of the Barnes collection as installed on the Parkway. Demonstrates how Barnes’s juxtapositions survive in a new space that reflects the transformation of a private vision into an institutional context.

- Bernstein, Roberta. “The Ensembles of Albert C. Barnes: Art as Experience.” Journal of Aesthetic Education 24 (3): 1–15. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1990.— Examines Barnes’s arrangements through the lens of John Dewey’s philosophy of experience. Highlights how his inclusion of hinges, ladles, and ironwork was not eccentricity but pedagogy, designed to democratize perception and erase hierarchies between fine and decorative art.

- Caamaño de Guzmán, María. El barroco mestizo en América: Escultura y devoción en los Andes. Madrid: Sílex, 2018.— Explores the hybrid styles of Hispano-American baroque, focusing on the Andes and Philippines. Provides context for the anonymous Bolivian painters and Hispano-Philippine sculptors mentioned in the essay, situating their work as simultaneously colonial and locally expressive.

- Chidester, David. Religion: Material Dynamics. Oakland: University of California Press, 2018.— Discusses how religious objects like stained glass are transformed when removed from liturgical settings into museums. Useful for framing the “uprooted” character of Maguire’s stained-glass windows and their re-contextualization from devotion to aesthetic contemplation.

- Fane, Diana, ed. Art and Identity in Spanish America. New York: Brooklyn Museum and Harry N. Abrams, 1996.— A key reference on colonial Latin American art, documenting how objects such as the vargueño embodied both European forms and indigenous contributions. Provides scholarly grounding for interpreting the vargueño as a portable stage of authority and hybridity.

- Fleming, David. Stained Glass in Catholic Philadelphia. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2020.— Chronicles stained-glass commissions in Philadelphia’s Catholic churches, many later dispersed into museum collections. Offers context for the Maguire collection, showing how local sacred art became uprooted into secular settings.

- Greenhalgh, Paul. The Persistence of Craft: The Applied Arts Today. London: Bloomsbury, 2020.— Explores the intersection of decorative art and modern aesthetics. Resonates with Barnes’s integration of ironwork and everyday utensils into his ensembles, treating them not as curiosities but as visual equals to painting.

- Hollander, Stacy C. American Anthem: Masterworks from the American Folk Art Museum. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2002.— Investigates how anonymous or vernacular artisans contributed to national artistic heritage. Relevant for the essay’s discussion of anonymous Bolivian painters and Hispano-Philippine sculptors, whose erasure mirrors the treatment of folk and colonial artisans more broadly.

- Kleinbauer, W. Eugene. Introduction to Medieval Stained Glass. New York: Harper & Row, 1971.— Classic introduction to stained-glass art as both narrative and abstraction. Supports the reading of Maguire’s stained glass as luminous color freed from symbol, while it acknowledges its devotional roots.

- Philanthropy Roundtable. Donor Intent Gone Wrong: The Battle for Control of the Barnes Art Collection. 2022. Short documentary. In Wisdom and Warnings series.— A concise 10-minute film examining how Barnes’s explicit instructions for educational, small-group engagement were overridden by broader institutional ambitions. It underscores the theme of uprooting through the betrayal of intent and reinforces how the displacement was as moral as it was spatial.

- Viau-Courville, Olivier. The Vargueño: Spanish Colonial Furniture and Power. Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 2021.— Focused monograph on the vargueño, explaining its symbolic role in the Spanish empire as a marker of authority and hybrid craftsmanship. Directly underpins the essay’s interpretation of the vargueño as suited to a monarch’s scribe and transformed by New World artisanship.