*

Author’s Note:

This essay is the second part of a trilogy that examines certainty, doubt, and ambivalence as conditions shaping our understanding of reality. It turns to doubt as both discipline and burden: a practice that unsettles claims of knowledge yet makes understanding possible. Here doubt is not treated as weakness but as a necessary stance within human communication. Its value lies not in closure but in keeping open the fragile line between appearance and reality. The trilogy begins with The Colors of Certainty and concludes with When All We Know Is Borrowed.

The Discipline of Doubt

Skepticism and doubt are often spoken of as if they were the same, yet they differ in essential ways. Skepticism inclines toward distrust: it assumes claims are false until proven otherwise. Doubt, by contrast, does not begin with rejection. It suspends judgment, while it withholds both assent and denial, so that questions may unfold. Skepticism closes inquiry prematurely; doubt preserves its possibility. Properly understood, inquiry belongs not to belief or disbelief, but to doubt.

This distinction matters because inquiry rarely follows a direct path to certainty. More often it is layered, restless, and incomplete. Consider the case of medicine. A patient may receive a troubling diagnosis and consult several physicians, while each offers a different prognosis. One may be more hopeful, another more guarded, yet none entirely conclusive. The temptation in such circumstances is to cling to the most reassuring answer or to dismiss all of them as unreliable. Both impulses distort the situation. Inquiry requires another path: to compare, to weigh, to test, and ultimately to accept that certainty may not be attainable. In this recognition, doubt demonstrates its discipline: it sustains investigation without promising resolution and teaches that the absence of finality is not failure but the condition for continued understanding.

Even within medicine itself, leaders recognize this tension. Abraham Verghese, together with other Stanford scholars, has pointed out that barely half of what is taught in medical schools proves directly relevant to diagnosis; the rest is speculative or unfounded. This observation does not aim to discredit medical education but rather to underline the need for a method that privileges verification over uncritical repetition. Clinical diagnosis, therefore, does not rest on an accumulation of certainties but on the constant practice of disciplined doubt: to question, to discard what is irrelevant, and to hold what is provisional while seeking greater precision.

History provides another vivid lesson in the figure of Galileo Galilei. When he trained his telescope on the night sky in 1609, he observed four moons orbiting Jupiter and phases of Venus that could only be explained if the planet circled the sun. These discoveries contradicted the Ptolemaic system, which for centuries had fixed the earth at the center of creation. Belief demanded obedience to tradition; skepticism might have dismissed all inherited knowledge as corrupt. Galileo’s path was different. He measured, documented, and published, while he knew that evidence had to be weighed rather than simply asserted or denied. The cost of this doubt was severe: interrogation, censorship, and house arrest. Yet it was precisely his refusal to assent too quickly—his suspension of judgment until the evidence was overwhelming—that made inquiry possible. Galileo shows how doubt can preserve the conditions of knowledge even under the heaviest pressure to believe.

Literature offers a parallel insight. In Shakespeare’s Hamlet, the young prince is confronted by the ghost of his murdered father, who demands vengeance. To believe would be to accept the apparition’s word at once and to kill the king without hesitation. To be skeptical would be to dismiss the ghost as hallucination or trickery. Hamlet does neither. He allows doubt to govern his response. He tests the ghost’s claim by staging a play that mirrors the supposed crime, as he watches the king’s reaction for confirmation. Hamlet’s refusal to act on belief alone, and his unwillingness to dismiss the ghost outright, illustrates the discipline of doubt. His tragedy lies not in doubting, but in stretching doubt beyond proportion, until hesitation itself consumes action. Shakespeare makes clear that inquiry requires balance: enough doubt to test what is claimed, enough resolve to act when evidence has spoken.

The demands of public life make the difference equally clear. In the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, citizens were asked to place immediate trust in official pronouncements or, conversely, to dismiss them as deliberate falsehoods. Belief led some to cling uncritically to each reassurance, however inconsistent; skepticism led others to reject all guidance as propaganda. Doubt offered another course: to ask what evidence supported the claims, to weigh early reports against later studies, and to accept that knowledge was provisional and evolving. The uncertainty was uncomfortable, but it was also the only honest response to a rapidly changing reality.

A similar pattern emerged after the September 11 attacks. Governments urged populations to choose: either support military intervention or stand accused of disloyalty. Belief accepted the justification for war at face value; skepticism dismissed all official claims as manipulation. Doubt, however, asked what evidence existed for weapons of mass destruction, what interests shaped the rush to invasion, and what alternatives were excluded from consideration. To doubt in such circumstances was not disloyalty but responsibility: the attempt to withhold assent until claims could be verified. These examples show that doubt is not passivity. It is the active discipline of testing what is said against what can be known: to resist the lure of premature closure.

Verification requires precisely this suspension: not the comfort of belief, nor the dismissal of skepticism, but the discipline of lingering within uncertainty long enough for proof to take shape. One might say that verification becomes possible only when belief is held in abeyance. Belief craves closure, skepticism assumes falsehood, but doubt stills the mind in the interval—where truth may draw near without the illusion of possession.

The same principle extends to the temptations of success and recognition. Success and fame resemble ashes: the hollow remains of a fire once bright but now extinguished, incapable of offering true joy to an inquiring mind. Ashes evoke a flame that once burned but has spent itself. So it is with fame: when the applause fades, only residue lingers. Belief, too, provides temporary shelter, yet it grows brittle when never tested. Recognition and conviction alike promise permanence, yet both prove fragile. A mind intent on inquiry cannot find rest in them. It requires something less visible, more enduring: the refusal to define itself too quickly, the discipline of anonymity.

Anonymity here does not mean retreat from the world. It means withholding assertion or purpose until knowledge has ripened. To declare too swiftly what one is—or what one knows—is to foreclose discovery. By necessity, the inquiring mind remains anonymous. It resists capture by labels or the scaffolding of recognition. Its openness is its strength. It stays attuned to what has not yet been revealed.

Our present age makes such discipline all the more urgent. Technology hastens every demand for certainty: headlines must be immediate, opinions instantaneous, identities reduced to profiles and tags. Social media thrives on belief asserted and repeated, rarely on doubt considered and tested. Algorithms reward speed and outrage, punishing hesitation as weakness and contradiction as betrayal. To cultivate doubt and anonymity is therefore a form of resistance. It shelters the subtlety of thought from the pressure of velocity and spectacle. It refuses to allow inquiry to be diminished into slogans or certainty compressed into catchphrases.

The discipline of doubt teaches that truth is never possessed, only pursued. Success, fame, and belief may glitter briefly, but they collapse into ashes. What endures is the quiet labor of questioning, the patience of remaining undefined until knowledge gathers form. To believe is to settle into residue; to doubt is to stand within the living fire. To question is to stir the flame; to believe is to collect the ashes.

*

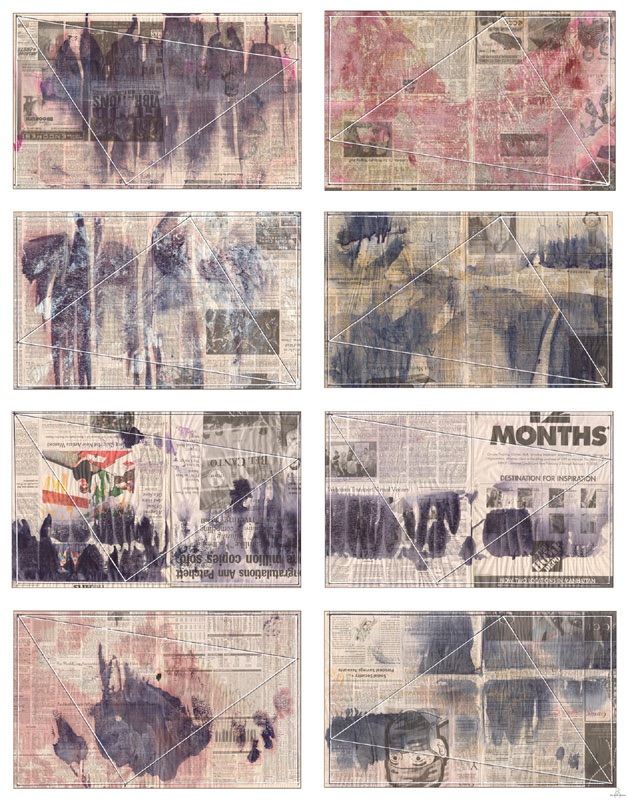

** Cover Design:

Ricardo Morín: Newsprint Series Nº 2 (2006). 51″ × 65″. Ink, white-out, and blotted oil paint on newsprint. From the Triangulation series.

Annotated Bibliography

- Arendt, Hannah: Between Past and Future. New York: Viking Press, 1961. (Arendt examines the importance of thinking without absolute supports and illuminates how the discipline of doubt resists political and social certainties).

- Bauman, Zygmunt: Liquid Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2000. (Bauman describes the fluidity and precariousness of certainties in modern life and reinforces the idea of doubt as a condition in the face of contemporary volatility).

- Berlin, Isaiah: The Crooked Timber of Humanity. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991. (Berlin analyzes the pluralism of values and the impossibility of single certainties and supports the need to live with unresolved tensions).

- Bitbol-Hespériès, Annie: Descartes’ Natural Philosophy. New York: Routledge, 2023. (Bitbol-Hespériès examines how Cartesian natural philosophy emerges from a constant exercise of methodical doubt; she offers a contemporary reading that links science and metaphysics in Descartes’ thought).

- Han, Byung-Chul: In the Swarm: Digital Prospects. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2017. (Han critiques the pressure of transparency and digital acceleration; he provides insights into how technology disfigures the patience required for doubt).

- Han, Byung-Chul: The Disappearance of Rituals. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2020. (Han explores how digital society weakens spaces of repetition and anticipation to highlight the urgency of recovering anonymity and slowness in inquiry).

- Croskerry, Pat, Cosby, Karen S., Graber, Mark, and Singh, Hardeep, eds.: Diagnosis: Interpreting the Shadows. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2017. (Croskerry, Cosby, Graber, and Singh address the cognitive complexity of diagnostic reasoning: they show how uncertainty is inherent in clinical practice and how disciplined doubt can reduce diagnostic error).

- Elstein, Arthur S., and Schwartz, Alan: Clinical Problem Solving and Diagnostic Decision Making: Selective Review of the Cognitive Literature. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002. (A landmark study in medical decision-making, it shows how diagnostic reasoning is less about static knowledge and more about methodical doubt and verification).

- Finocchiaro, Maurice: Retrying Galileo, 1633–1992. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005. (Finocchiaro explores the trials and historical reinterpretations of Galileo’s case; he shows how scientific doubt clashed with religious authority and how it has been re-evaluated in modernity).

- Gaukroger, Stephen: Descartes: An Intellectual Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002. (An intellectual biography that situates Descartes in the cultural context of the seventeenth century and illuminates how Cartesian doubt was also a strategy against religious and scientific tensions).

- Garber, Daniel: Descartes Embodied: Reading Cartesian Philosophy through Cartesian Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. (Garber analyzes the close relationship between Descartes’ science and his philosophical method and underscores how scientific practice reinforced the discipline of doubt).

- Graber, Mark L., Gordon D. Schiff, and Hardeep Singh: The Patient and the Diagnosis: Navigating Clinical Uncertainty. New York: Oxford University Press, 2020. (Graber explores how physicians manage uncertainty and emphasizes that precision in diagnosis emerges from structured methods rather than unquestioned knowledge).

- Machamer, Peter, ed.: The Cambridge Companion to Galileo. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. (In this collection of updated essays presenting Galileo’s work from historical, philosophical, and political perspectives, Machamer illuminates how empirical doubt transformed cosmology).

- Nussbaum, Martha: Political Emotions: Why Love Matters for Justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013. (Nussbaum examines how liberal institutions can responsibly cultivate public emotions—such as love, tolerance, and solidarity. Her arguments enrich the section of the essay on civic-life, which shows how emotional cultivation, beyond belief or skepticism, supports societal inquiry).

- Popkin, Richard: The History of Scepticism: From Savonarola to Bayle. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003. (In this historical study of skepticism, Popkin shows how skepticism evolved between radical distrust and the discipline of inquiry).

- Shakespeare, William: Hamlet. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003. (This play offers a literary embodiment of doubt as an ambivalent force: it functions both as the engine of inquiry and the risk of paralysis).

- Shea, William, and Artigas, Mariano : Galileo in Rome: The Rise and Fall of a Troublesome Genius. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003. (An accessible and well-documented narrative of Galileo’s conflict with the Church; it illustrates how persistence in verifying doubt had vital and political consequences).

- Verghese, Abraham, Saint, Sanjay, and Cooke, Molly: “Critical Analysis of the ‘One Half of Medical Education Is Wrong’ Maxim.” Academic Medicine 86, no. 4 (2011): 419–423. (Authored by Stanford-affiliated leaders in medical education, the report argues that much of medical teaching lacks direct relevance to diagnostic accuracy and underscores the necessity of disciplined doubt and re-evaluation).