*

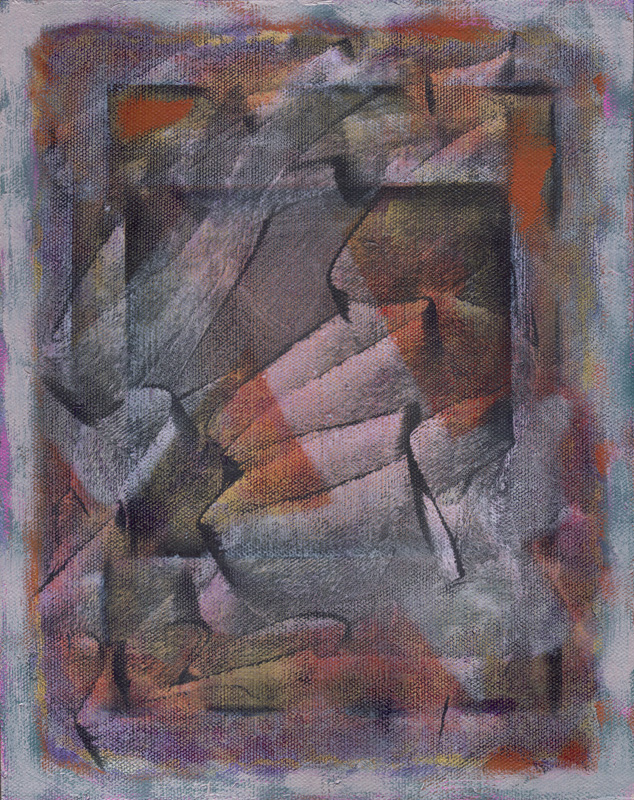

Still Thirty-three: When All We Know Is Borrowed

Oil on linen & board, 15″ x 12″x 1/2″

2012.

Author’s Note:

This essay concludes the trilogy begun with The Colors of Certainty and continued with The Discipline of Doubt. It reflects on perception, ambiguity, and ambivalence as conditions that complicate our access to truth, especially in an age of mistrust. The trilogy as a whole asks how certainty, doubt, and ambivalence each shape the paradoxes of human understanding—and how reality is always encountered in fragments, never in full possession.

The purpose of this essay is not to resolve these tensions but to articulate them. Its value lies less in offering solutions than in clarifying the paradoxes that underlie our shared attempts to understand reality.

Ricardo Morín, Bala Cynwyd, Pa. August 30, 2025.

Abstract:

This essay examines perception, ambiguity, and belief as distinct but interrelated conditions that shape human access to reality. Ambiguity marks the instability of meaning; perception denotes our filtered and partial contact with the world; and ambivalence names the paradoxical ground on which truth is sought. Ambivalence sustains the search even as it undermines the certainty that truth has been attained. Writing and reading reveal these dynamics with particular clarity. Through writing, thought evolves; the writer participates in this evolution and discovers that meaning may remain both untranslatable and questionable. Yet this very incompleteness expands understanding, even when what is grasped cannot be fully shared. Extending beyond communication, the essay suggests that reality itself is encountered only in fragments—through gestures, silences, and misperceptions that weaken the line between appearance and reality. Artificial intelligence illustrates this condition in two ways: as a tool, it amplifies practical doubts about authorship and authenticity; as a mirror, it reflects the deeper ambivalence that precedes it. The essay concludes that ambivalence is not a detour from truth but the paradox through which truth, if it arises at all, briefly appears.

~

Perception

The word perception carries within it a history that mirrors the shifting ways in which cultures have understood reality. From the Latin perceptio, it meant first a “taking in,” a “gathering,” or even a “harvest.” To perceive was to collect impressions, as one might collect grain from a field: passive in form, but active in intent.

In Greek thought, perception was bound to aisthēsis—sensation was the contact one felt with the world. Here it stood closer to the arts, to the immediacy of feeling, than to the systematic reasoning of philosophy.

During the Middle Ages, particularly in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, Aristotle’s writings were recovered and incorporated into Christian scholastic thought. What had been a pagan philosophy of sensation and intellect was reinterpreted by thinkers such as Thomas Aquinas within a theological framework of knowledge. Perception was defined as the reception of sensory data by the intellect, a necessary stage through which sensation was elevated into understanding.

With the rise of modern philosophy, the term fractured. For Descartes, perception could deceive; for Locke, it formed the foundation of experience; for Kant, it was structured by categories that both opened and constrained our access to reality. By then perception had already become ambivalent: indispensable for knowing, but never certain in its truth.

Today the word extends further still, connoting not only sensation but also interpretation, bias, and opinion. To say “that is your perception” is no longer to affirm contact with the real but to indicate distance, distortion, or subjectivity. The evolution of the word reveals a semantic instability that parallels the essay’s claim: our access to reality is always shaped by ambivalence. What perception grants, it also unsettles.

Ambivalence, and the Limits of Truth

Perception is never a simple act of receiving what is already there. It is always mediated by memory, expectation, and predisposition. In every exchange—whether in words on a page or in silence between two people—meaning shifts, unsettled and provisional. From this shifting ground arises ambiguity, and from ambiguity, the unease that unsettles belief.

For the reader, this instability is unavoidable. Every response, even silence, is colored by trust or mistrust, sympathy or suspicion, openness or fatigue. Rarely does a reader approach a text in innocence, for every act of reading is shaped by assumptions that condition the reception of words.

The author is not exempt from this interpretive burden. The act of writing does not end with publication but continues in the uncertain work of reading readers. A pause in conversation, a fleeting acknowledgment, or a lack of reply can be interpreted as disinterest, disapproval, or indifference. In this way, writing interprets interpretations and multiplies the layers of ambiguity until the meaning of the work appears not only untranslatable but also questionable. Yet it is precisely through this reflection that writing continues, for without it thought cannot develop. By persevering in this process, the writer participates in a widening of understanding, even when that understanding cannot be fully shared.

Such uncertainty is not a flaw of communication but part of its structure. Anyone who seeks to understand through writing must accept that clarity will always be provisional and that expression will always fall short. The act of putting thought into words reveals the distance between intention and reception, but it also creates the possibility of seeing reality from new angles. Even when what is expressed cannot be communicated in full, the process itself enlarges understanding and deepens awareness of what is partial and in flux.

Ambivalence, therefore, is not hesitation but the paradoxical condition in which the search for meaning takes place. It joins conviction and doubt, the desire for certainty and the recognition of its limits. To write within ambivalence is to continue searching even when the result cannot be communicated without loss. This condition—and not the illusion of final clarity—enables thought to move forward.

Truth, if it is ever reached, emerges despite the unstable ground of perception and ambiguity. We arrive at it in spite of ourselves, our tensions, and our limitations. It is not only major errors that weaken certainty: a nuance misperceived, a pause misunderstood, or an ambiguous gesture may also diminish trust. Daily experience shows that the line between appearance and reality is too thin to provide lasting assurance.

But this tension is not limited to writing or reading. It extends more deeply, into our relation with reality itself. Ambivalence is not only a feature of communication but also a feature of existence. To perceive is always to partake of the world incompletely; to live is to do so under conditions of partial presence. At times we see clearly, at other times dimly, and often not at all. This rhythm of presence and withdrawal marks every relationship—between persons, between societies, and even between humanity and nature.

Technology has sharpened our awareness of this condition. Artificial intelligence, for example, dramatizes the instability already present in human perception. As a tool, it enables refinement of expression while amplifying doubts about authorship and authenticity. As a mirror, it reflects the deeper ambivalence that precedes it and shapes all mediation. Thus AI does not diminish thought but magnifies the unease that accompanies human access to reality: the sense that what is offered is incomplete, unreliable, and never fully participatory.

The task, then, is not to eliminate ambiguity but to recognize it as part of reality itself. Perception is interpretive, belief is unstable, and mistrust is a constant companion. Ambivalence is not a detour from truth but the path along which truth—if it comes at all—must travel. The challenge is not to restore a certainty that never existed but to learn to live within partial participation, to accept that what we call reality is always encountered in fragments.

In this sense, perception, ambiguity, and belief will always remain unsettled. The writer cannot control how words are read, nor can the reader fully grasp what was meant. No one can claim full possession of reality. Every relation to the world depends on fragile conditions, where appearance and reality touch without ever coinciding. If truth appears at all, it does so briefly and incompletely, arising only through ambivalence. Yet ambivalence itself is a paradoxical condition: it sustains our search for truth even as it undermines the certainty we long to possess. Truth cannot confer ownership because it never rests.

Annotated Bibliography

- Arendt, Hannah: The Human Condition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1958. (Arendt analyzes action, labor, and work as distinct ways of engaging reality. Her distinction between appearance and reality, and her insistence that truth emerges through shared human activity, is directly relevant to the essay’s theme of perception and ambivalence.)

- Gadamer, Hans-Georg: Truth and Method. New York: Continuum, 1975. (In this foundational text in hermeneutics, Gadamer explores how understanding arises through interpretation rather than objectivity. His view that truth is approached dialogically supports the essay’s claim that truth emerges “within ambivalence rather than beyond it.”)

- Girard, René: Deceit, Desire, and the Novel. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1965. (Girard’s theory of mimetic desire shows how interpretation, desire, and misunderstanding shape human relations. His work underlines the fragility of belief and the unstable boundary between appearance and reality.)

- Nussbaum, Martha: Political Emotions: Why Love Matters for Justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013. (Nussbaum argues that public emotions—such as love, compassion, and solidarity—are essential to sustaining justice. Her insights reveal how belief is fragile and shaped by interpretation; it resonates with the essay’s concern about trust, ambivalence, and human participation in reality.)

- Turkle, Sherry: Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other. New York: Basic Books, 2011. (Turkle investigates how technology mediates human relationships and perceptions. Her work frames AI as a mirror of doubt; it shows how mediation both enables connection and erodes authenticity—an idea central to the essay.)