Allegory, Virtue, and the Measure of Governance

*

Author’s Note:

This installment marks a transition in the Unmasking Disappointment series. The chapters that follow move from symbolic orientation to institutional diagnosis—from the ethical measures by which governance may be assessed to the historical mechanisms through which those measures were steadily displaced.

The opening chapters do not propose an ideal government as a program, nor do they advance allegory as metaphysical instruction. They establish, instead, a standard of measure. Without some articulation of justice, restraint, and judgment as relational constraints, disappointment risks collapsing into mere grievance or retrospective outrage. Allegory appears here not as escape from political reality, but as a means of identifying when political language has been emptied of substance.

The chapters that follow trace how resentment, military authority, and party asymmetry gradually supplanted those constraints in Venezuela. What emerges is not a singular rupture but an accumulation: ideals invoked without limit, institutions mobilized without restraint, and power exercised without symmetry. Disappointment, in this sense, is not an emotional response but a structural outcome—one produced when virtue survives only as symbol, no longer as practice.

*

On ethical geometry before political distortion

Chapter VII

The Allegorical Mode

Resistance to authority often makes use of symbolism that requires interpretation and thereby detaches meaning from responsibility. In the spirit of Plato, I propose that the true philosopher is an inverted allegorist. Rather than merely deciphering symbols, the philosopher distinguishes between what signifies and what governs.

Symbols and allegories are not mere reflections of the material world but serve as gateways to something beyond it. Allegory functions as recognition only where symbols have ceased to orient conduct—an orientation toward that with which the philosopher strives to align.

~

*

Chapter VIII

*

The Ideal Government and the Power of Virtue

~

~

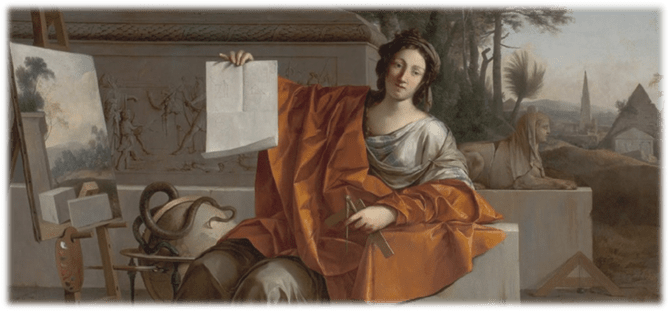

Allégorie de la Géométrie, by Laurent de La Hyre (1649), evokes a conception of ideal government understood as a geometry of virtues, in which balance depends on proportion rather than invocation. Justice, temperance, and wisdom form a triad whose significance lies not in their enumeration but in the relations they establish. As in geometry, stability is maintained only so long as those proportions hold.

Just as the philosopher moves beyond symbols toward discernment, so too must governance be assessed by standards not governed by the whims of power. In the spirit of Plato’s Forms, an ideal government reflects justice, temperance, and wisdom—principles that do not fluctuate with circumstance. Such a government stands in contrast to politics organized around power alone.

The concept of virtue in governance transcends moral abstraction; it operates as a relational condition between rulers and the governed. Virtue does not belong exclusively to either, but emerges in the form that relation takes and the limits it sustains. Where virtue operates, governance is not organized around the accumulation of power but around constraints that regulate its exercise—justice to restrict arbitrariness, temperance to contain excess, and wisdom to discipline decision.

Government understood as a form structured by virtue exposes abuses of power not as exceptional deviations but as structural failures. When symbols such as equity or plurality are detached from their regulating functions, they become available for use as instruments of control. Where virtue retains an operative role, such symbols cease to obscure power and resume their function as limits on its exercise.

Chavismo, as it emerged under Hugo Chávez and continued under Nicolás Maduro, stands in direct contrast to these conditions. Although the regime relied extensively on the language of justice and equity, those references ceased to function as constraints on power. Symbols associated with virtue were detached from their regulating roles and redeployed as mechanisms of legitimization. Governance thus persisted in the vocabulary of virtue while operating without its limiting functions.

Virtuous governance assumes the form of a balanced structure: one not governed by the current of power but constrained by justice. Such a system does not privilege the will of the ruler over the common good, nor does it rely on appeals that fluctuate with circumstance. Where these constraints hold, order becomes possible—not as aspiration, but as condition.