*

Ricardo F. Morín

Oakland Park, F.

December 12, 2025

Author’s Note

Reflections from previous chapters eventually lead to a more historical inquiry, in which the following archive, Chronicles of Hugo Chávez, becomes another lens through which I approach the Venezuelan experience.

Chapter VI

*

Chronicles of Hugo Chávez

~

1

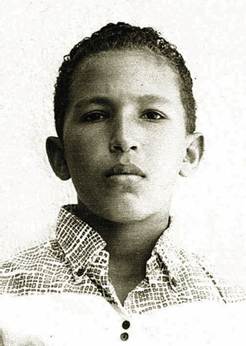

Hugo Chávez, who spearheaded the Bolivarian Revolution, was born on July 28, 1954, in Sabaneta, Venezuela. He died on March 5, 2013, at 4:25 p.m. VET (8:55 p.m. UTC) in Caracas, at the age of 58. As the leader of the revolution, Chávez left a discernible imprint on Venezuela’s political history. To reconstruct this history is to revisit a landscape whose consequences continue to shape Venezuelan life.

At the core of Chavismo lies a deliberate fusion of nationalism, centralized power, and military involvement in politics. This fusion shaped his vision for a new Venezuela, one that would be fiercely independent and proudly socialist.

~

2

Hugo Chávez’s childhood was spent in a small town in Los Llanos, in the northwestern state of Barinas. This region has a history of indigenous chiefdoms (i.e., “leaderships,” “dominions,” or “rules”) dating back to pre-Columbian times. [1] Chávez was the second of six brothers, and his parents struggled to provide for the large family. As a result, he and his older brother Adán were sent to live with their paternal grandmother, Rosa Inés, in the city of Barinas. After her death, Chávez honored his grandmother’s memory with a poem; it concludes with a stanza that reveals the depth of their bond:

Entonces, / abrirías tus brazos/ y me abrazarías/ cual tiempo de infante/ y me arrullarías/ con tu tierno canto/ y me llevarías/ por otros lugares/ a lanzar un grito/ que nunca se apague. [2]

[Author’s translation: Then, / you would open your arms / and draw me in / as if returned to childhood / and you would steady me / with your tender voice / and you would carry me / to other places / to release a cry / that would not be extinguished].

3

In his second year of high school, Chávez encountered two influential teachers, José Esteban Ruiz Guevara and Douglas Ignacio Bravo Mora, both of whom provided guidance outside the regular curriculum. [3][4] They introduced Chávez to Marxism-Leninism as a theoretical framework, sparking his fascination with the Cuban Revolution and its principles—a turning point more visible in retrospect than it could have been in the moment.

4

At 17, Chávez enrolled in the Academia Militar de Venezuela at Fuerte Tiuna in Caracas, where he hoped to balance military training with his passion for baseball. He dreamed of becoming a left-handed pitcher, but his abilities did not match his ambition. Despite his initial lack of interest in military life, Chávez persisted in his training, graduating from the academy in 1975 near the bottom of his class.

5

Chávez’s military career began as a second lieutenant; he was tasked with capturing leftist guerrillas. As he pursued them, he found himself identifying with their cause and believed they fought for a better life. But by 1977, Chávez was prepared to abandon his military career and join the guerrillas. Seeking guidance, he turned to his brother Adán, who persuaded him to remain in the military by insisting, “We need you there.” [5] Chávez now felt a sense of purpose and understood his mission as a calling. In 1982, he and his closest military associates formed the Bolivarian Revolutionary Movement-200: they aimed to spread their interpretation of Marxism within the armed forces and ultimately hoped to stage a coup d’état. [6]

6

On February 4, 1992, Lieutenant Chávez and his military allies launched a revolt against the government of President Carlos Andrés Pérez. Their rebellion, however, was swiftly quashed. Surrounded and outnumbered, Chávez surrendered at the Cuartel de la Montaña, the military history museum in Caracas, near the presidential palace, on the condition that he be allowed to address his companions via television. He urged them to lay down their arms and to avoid further bloodshed. He proclaimed, « Compañeros, lamentablemente por ahora los objetivos que nos planteamos no fueron logrados . . . » [Author’s translation: “Comrades, unfortunately, our objectives have not been achieved… yet,”].[7] The broadcast marked the beginning of his political ascent. His words resonated across the nation and sowed the seeds of his political future.

~

7

In 1994, newly elected President Rafael Caldera Rodríguez pardoned him. [8] With this second chance, Chávez founded the Movimiento V República (MVR) in 1997 and rallied like-minded socialists to his cause. [9] Through a campaign centered on populist appeals, he secured an electoral victory at age 44.

8

In his first year as President, Chávez enjoyed an 80% approval rating. His policies sought to eradicate corruption in the government, to expand social programs for the poor, and to redistribute national wealth. Jorge Olavarría de Tezanos Pinto, initially a supporter, emerged by the end of the elections as a prominent voice of the opposition. Olavarría accused Chávez of undermining Venezuela’s democracy through his appointment of military officers to governmental positions. [10] At the same time, Chávez was drafting a new constitution, which allowed him to place military officers in all branches of government. The new constitution, ratified on December 15, 1999, paved the way for the “mega elections” of 2000, in which Chávez secured a term of six years. Although his party failed to gain full control of the Asamblea Nacional (National Assembly), it passed laws by decree through the mechanism of the Leyes Habilitantes (Enabling Laws). [11][12] Meanwhile, Chávez initiated reforms to reorganize the State‘s institutional structure, but the constitution’s requirements were not met. The appointment of judges to the new Corte Suprema de Justicia [CSJ] was carried out without rigor and raised concerns about its legitimacy and competence. Cecilia Sosa Gómez, the outgoing Corte Suprema de Justicia president, declared the rule of law “buried” and the court “self-dissolved.” [13][14]

9

Although some Venezuelans saw Chávez as a refreshing alternative to the country’s unstable democratic system, which had been dominated by three parties since 1958, many others expressed concern as the Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela (PSUV) consolidated power and became the sole governing party. [15] Legislative and executive powers were increasingly centralized, and the narrowing of judicial guarantees limited citizens’ participation in the democratic process. Chávez’s close ties with Fidel Castro and his desire to model Venezuela after Cuba’s system—dubbed VeneCuba—raised alarm. [16] He silenced independent radio broadcasters, and he antagonized the United States and other Western nations. Instead, he strengthened ties with Iraq, Iran, and Libya. Meanwhile, domestically, his approval rating had plummeted to 30%, and anti-Chávez demonstrations became a regular occurrence.

10

On April 11, 2002, a massive demonstration of more than a million people converged on the presidential palace to demand President Chávez’s resignation. The protest turned violent when agents of the National Guard and masked paramilitaries opened fire on the demonstrators. [17] The tragic event—the Puente Llaguno massacre—sparked a military uprising that led to Chávez’s arrest and to the installation of a transitional government under Pedro Francisco Carmona Estanga. [18] Carmona’s leadership, however, was short-lived; he swiftly suspended the Constitution, dissolved the Asamblea Nacional and the Corte Suprema, and dismissed various officials. Within forty-eight hours, the army withdrew its support for Carmona. The vice president, Diosdado Cabello Rondón, was reinstated as president and promptly restored Chávez to power. [19]

11

The failed coup d’état enabled Chávez to purge his inner circle and to intensify his conflict with the opposition. In December 2002, Venezuela’s opposition retaliated with a nationwide strike aimed at forcing Chávez’s resignation. The strike targeted the state oil company Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA), which generated roughly 80% of the country’s export revenues. [20] Chávez responded by dismissing its 38,000 employees and replacing them with loyalists. By February 2003, the strike had dissipated, and Chávez had once again secured control over the country’s oil revenues.

12

From 2003 to 2004, the opposition launched a referendum to oust Chávez as president, but soaring oil revenues, which financed social programs, bolstered Chávez’s support among lower-income sectors. [21] By the end of 2004, his popularity had rebounded, and the referendum was soundly defeated. In December 2005, the opposition boycotted the elections to the National Assembly and protested against the Consejo Nacional Electoral (National Electoral Council) (CNE). [22] As anticipated in view of the opposition boycott, Chávez’s coalition capitalized on the absence of an effective opposition and strengthened its grip on the Assembly. [23] By that point, legislative control rested almost entirely with Chávez’s coalition. What followed was not a departure from this trajectory, but its extension through formal policy.

13

In December 2006, Chávez secured a third presidential term, a victory that expanded the scope of executive initiative. He nationalized key industries—gold, electricity, telecommunications, gas, steel, mining, agriculture, and banking—along with numerous smaller entities. [24][25][26][27][28][29] Chávez also introduced a package of constitutional amendments designed to expand the powers of the executive and to extend its control over the Banco Central de Venezuela (BCV). In a controversial move, he unilaterally altered property rights and allowed the state to seize private real estate without judicial oversight. Furthermore, he proposed becoming president for life. In December 2007, however, the National Assembly narrowly rejected the package of sweeping reforms.

14

In February 2009, Chávez reintroduced his controversial proposals and succeeded in advancing them. Following strategic counsel from Cuba, he escalated the crackdown on dissent. [30] He ordered the arrest of elected opponents and shut down all private television stations.

15

In June 2011, Chávez announced that he would undergo surgery in Cuba to remove a tumor, a development that sparked confusion and concern throughout the country. [31] As his health came under increasing scrutiny, more voters began to question his fitness for office. Yet, in 2012, despite his fragile health, Chávez campaigned against Henrique Capriles and secured a surprise presidential victory. [32]

~

16

In December 2012, Chávez underwent his fourth surgery in Cuba. Before departing Venezuela, he announced his plan for transition and designated Vice President Nicolás Maduro as his successor, alongside a powerful troika that included Diosdado Cabello [military chief] and Rafael Darío Ramírez Carreño [administrator of PDVSA]. [33][34][35] Following the surgery, Chávez was transferred on December 11 to the Hospital Militar Universitario Dr. Carlos Arvelo (attached to the Universidad Militar Bolivariana de Venezuela, or UMBV) in Caracas, where he remained incommunicado, further fueling speculation and rumors. Some government officials dismissed reports of assassination, while others, including former Attorney General Luisa Ortega Díaz, claimed he had already died on December 28. [36] Maduro’s cabinet vehemently refuted these allegations and insisted that no crime had been committed. Amidst the uncertainty, Maduro asked the National Assembly to postpone the inauguration indefinitely. This further intensified political tensions.

17

The National Assembly acquiesced to Maduro and voted to postpone the inauguration. Chávez succumbed to his illness on March 5. His body was embalmed in three separate stages without benefit of autopsy, which further fueled suspicions and conspiracy theories. Thirty days later, Maduro entered office amid sustained political uncertainty. [37] The implications of this transition extend beyond chronology; they shape the conditions examined in the chapters that follow in this series, which comprises 19 chapters, miscellaneous rubrics, and an appendix.

~

Endnotes:

§ 2

[1] Charles S. Spencer and Elsa M. Redmond, Prehispanic Causeways and Regional Politics in the Llanos of Barinas, Venezuela (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017). Abstract: “…relacionados con la dinámica política de la organización cacical durante la fase Gaván Tardía.” Published in Latin American Antiquity, vol. 9, no. 2 (June 1998): 95-110. https://doi.org/10.2307/971989

[2] Rosa Miriam Elizalde y Luis Báez, Chávez Nuestro, (La Habana: Casa Editora Abril, 2007), 367-369. https://docs.google.com/file/d/0BzEKs4usYkReRVdWSG5LQkFYQ3c/edit?pli=1&resourcekey=0-yHaK7-YkA47nelVs-7JuBQ

§ 3

[3] “The Hugo Chávez Show,” PBS Front Line, November 19, 2008. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/hugochavez/etc/ex2.html

[4] L’Atelier des Archive, “Interview du révolutionnaire: Douglas Bravo au Venezuela [circa 1960]” (Transcript: “… conceptos injuriosos en contra de la revolución cubana …” [timestamp 1;11-14]), YouTube, October 14, 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1cx2D5VM8VM

§ 5

[5] “Hugo Chavez Interview,”YouTube, transcript excerpt and time stamp unavailable: Original quote in Spanish (translated by the author): “. . . , if not, maybe I’ll leave the Army, no, you can’t leave, Adam told me so, no, we need you there, but who needs me?” Retrieved October 12, 2023.

[6] Dario Azzellini and Gregory Wilpert, “Venezuela, MBR–200 and the Military Uprisings of 1992,”in The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest (Wiley 2009). https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/9781405198073.wbierp1525

§ 6

[7] “Declarations in a Nationwide Government-Mandated Broadcast,” BancoAgrícolaVe, YouTube, February 4, 1992. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_QqaR1ZjldE

§ 7

[8] Maxwell A. Cameron and Flavie Major, “Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez: Savior or Threat to Democracy?,” Latin American Research Review, vol. 36, no. 3, (2001): 255-266. https://www.proquest.com/docview/218146430?sourcetype=Scholarly%20Journals

[9] Gustavo Coronel, “Corruption, Mismanagement, and Abuse of Power in Hugo Chávez’s Venezuela,” Center for Global Liberty & Prosperity: Development Policy Analysis, no. 2 (CATO Institute, November 27, 2006). https://www.issuelab.org/resources/2539/2539.pdf.

§ 8

[10] “Jorge Olavarría Ante El Congreso Bicameral [July 5,1999],” YouTube. https://youtu.be/_OkqNn8VF-Y?si=Cvuh4Vk391_0Pnut . Accessed January 9, 2025.

[11] Mario J. García-Serra, “The ‘Enabling Law’: The Demise of the Separation of Powers in Hugo Chavez’s Venezuela,” University of Miami Inter-American Law Review, vol.32, no. 2, (Spring – Summer, 2001): 265-293. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40176554

[12] “Venezuela: Chávez Allies Pack Supreme Court,” Human Rights Watch, December 13, 2004. https://www.hrw.org/news/2004/12/13/venezuela-chavez-allies-pack-supreme-court

[13] “Top Venezuelan judge resigns,” BBC News, August 25, 1999. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/429304.stm

[14] “Suprema Injusticia: ‘These are corrupt judges,” Organización Transparencia Venezuela. https://supremainjusticia.org/cecilia-sosa-gomez-these-are-corrupt-judges/

§ 9

[15] “United Socialist Party of Venezuela,” PSUV. http://www.psuv.org.ve/

[16] “Venezuela and Cuba, ‘VeneCuba,’ a single nation,” The Economist, February 11, 2010. https://www.economist.com/the-americas/2010/02/11/venecuba-a-single-nation

§ 10

[17] “Photographs reveal the truth about Puente Llaguno massacre,” April 11, 2002, YouTube. https://youtu.be/NvP7cL-7KL4?si=cUpMAv0myAWH5UWP

[18] “Pedro Carmona Estanga cuenta su verdad 21 años después,” El Nacional de Venezuela. https://www.elnacional.com/opinion/pedro-carmona-estanga-cuenta-su-verdad-21-anos-despues/

[19] “Diosdado Cabello Rondón:Narcotics Rewards Program: Wanted,” U.S. Department of State. https://www.state.gov/bureau-of-international-narcotics-and-law-enforcement-affairs/releases/2025/01/diosdado-cabello-rondon

§ 11

[20] Marc Lifsher, “Venezuela Strike Paralyzes State Oil Monopoly PdVSA,” Wall Street Journal, December 6, 2002. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB1039101526679054593

§ 12

[21] “Socialism with Cheap Oil,” The Economist, December 30, 2008. https://www.economist.com/the-americas/2008/12/30/socialism-with-cheap-oil

[22] “Venezuela: Increased Threats to Free Elections; New Electoral Body Puts Reforms at Risk,” Human Rights Watch, June 22, 2023 7:00AM. https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/06/22/venezuela-increased-threats-free-elections

[23] Juan Forero, “Chávez Grip Tightens as Rivals Boycott Vote,” The New York Times, December 5, 2005. https://www.nytimes.com/2005/12/05/world/americas/chavezs-grip-tightens-as-rivals-boycott-vote.html?referringSource=articleShare

§ 13

[24] Louise Egan, “Chavez to nationalize Venezuelan gold industry,” Reuters, August 17, 2011, 2:40 PM. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-venezuela-gold/chavez-to-nationalize-venezuelan-gold-industry-idUSTRE77G53L20110817/

[25] Juan Forero, “Chavez Eyes Nationalized Electrical, Telcom Firms,” Reuters, January 9, 2007, 6:00 AM ET. https://www.npr.org/2007/01/09/6759012/chavez-eyes-nationalized-electrical-telcom-firms

[26] James Suggett, “Venezuela Nationalizes Gas Plant and Steel Companies, Pledges Worker Control,” Venezuelanalysis, May 23, 2009. https://venezuelanalysis.com/news/4464/

[27] David Brunnstrom, “Factbox: Venezuela’s nationalizations under Chavez,” Reuters, October 7, 2012, 10:51 PM. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-venezuela-election-nationalizations/factbox-venezuelas-nationalizations-under-chavez-idUSBRE89701X20121008/

[28] Frank Jack Daniel–Analysis–, “Food, farms the new target for Venezuela’s Chavez,” Reuters, March 5, 2009, 6:06 PM EST. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-venezuela-chavez-analysis-sb/food-farms-the-new-target-for-venezuelas-chavez-idUSTRE5246OO20090305/

[29] Daniel Cancel, “Chavez Says He Has No Problem Nationalizing Banks,” Bloomberg, November 29, 2009, 15:02 GMT-5. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2009-11-29/chavez-says-he-has-no-problem-nationalizing-banks

§ 14

[30] Angus Berwick, “Special Report: How Cuba taught Venezuela to quash military dissent,” Reuters, August 22, 2019, 8:22 AM ET. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-venezuela-cuba-military-specialreport/special-report-how-cuba-taught-venezuela-to-quash-military-dissent-idUSKCN1VC1BX/

§ 15

[31] Robert Zeliger, Passport: “Hugo Chavez’s medical mystery,” Foreign Policy, June 24, 2011, 10:20 PM. https://foreignpolicy.com/2011/06/24/hugo-chavezs-medical-mystery/

[32] Juan Forero, “Hugo Chavez Beats Henrique Capriles,” The Washington Post, October 7, 2012. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/venezuelans-flood-polls-for-historic-election-to-decide-if-hugo-chavez-remains-in-power/2012/10/07/d77c461c-10c8-11e2-9a39-1f5a7f6fe945_story.html

§ 16

[33] Bryan Winter and Ana Flor, “Exclusive: Brazil wants Venezuela election if Chavez dies – sources,” Reuters, January 14, 2013, 9:12 PM EST, updated 12 years ago. https://www.reuters.com/article/cnews-us-venezuela-chavez-brazil-idCABRE90D12320130114/

[34] “Venezuela National Assembly chief: Diosdado Cabello,” BBC News, March 5, 2013. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-20750536

[35] “Rafael Darío Ramírez Carreño of Venezuela Chair of Fourth Committee,” United Nations, BIO/5031*-GA/SPD/630; 25 September 2017. https://press.un.org/en/2017/bio5031.doc.htm

[36] Ludmila Vinogradoff, “La exfiscal Ortega confirma que Chávez murió dos meses antes de la fecha anunciada,” ABCInternacional, actualizado Julio 16, 2018, 12:44 https://www.abc.es/internacional/abci-confirman-chavez-murio-meses-antes-fecha-anunciada-201807132021_noticia.html?ref=https://www.google.com/

§ 17

[37] “Cuerpo de Chávez fue tratado tres veces para ser conservado: … intervenido con inyecciones de formol para que pudiera ser velado,” El Nacional De Venezuela – Gda, Enero 27, 2024, 05:50, actualizado Marzo 22, 2013, 20:51. https://www.eltiempo.com/amp/archivo/documento/CMS-12708339

~