A diagnostic study of how public life continues to function when judgment is limited and conditions remain unsettled

*

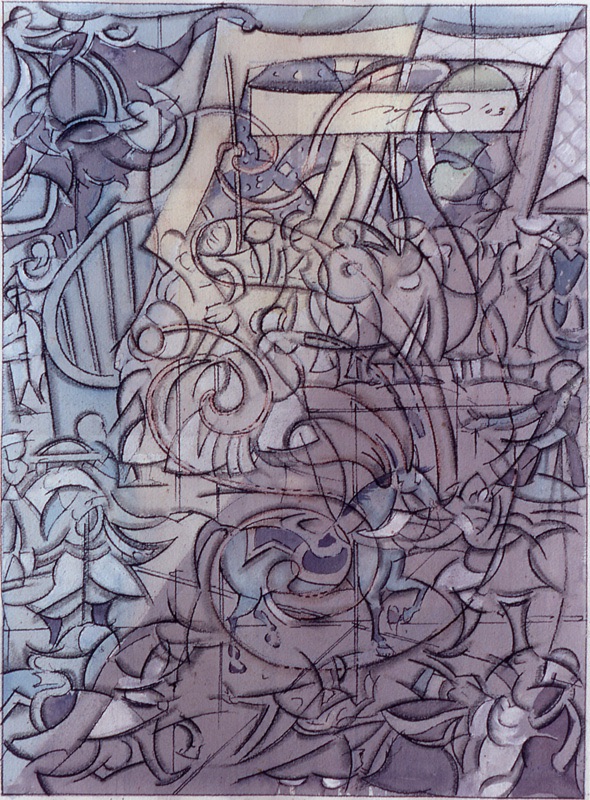

Mantra: Domains of Action

21” x 28.5”

Watercolor, graphite, wax crayons,

ink and gesso on paper

2003

Note:

Nothing I say belongs to the painting.

The painting does not need words.

It already speaks in its own medium, to which language has no equivalent.

By Ricardo F. Morín

December 18, 2025

Oakland Park, Fl

Preface

This work was not written to advance a position or to resolve a debate. It emerged from sustained attention to conditions that could not be ignored without distortion. Writing, in this sense, is not an expression of purpose, but a consequence of awareness.

The pages that follow do not claim authority through expertise or urgency. They proceed from the recognition that judgment must often act under incomplete conditions, and that clarity, when it appears, does so gradually and without assurance. What is offered here is not a conclusion, but a continuation: an effort to remain faithful to what can be observed when attention is sustained.

This study does not proceed from constitutional expertise, institutional authority, or professional proximity to governance. It proceeds from observation. Its claims arise from sustained attention to how public life continues to function under conditions in which judgment is constrained, information remains incomplete, and decisions must nonetheless be made.

In fields where credentialed knowledge often determines legitimacy, writing from outside formal authority can invite dismissal before engagement. That risk is real. Yet the conditions examined here are not confined to technical domains. They are encountered daily by citizens, officials, institutions, and systems alike. Judgment under uncertainty is not a specialized activity; it is a shared condition.

The absence of formal expertise does not exempt this work from rigor. It requires a different discipline: restraint in assertion, precision in description, and fidelity to what can be observed without presuming mastery. The analysis does not claim to resolve constitutional questions or prescribe institutional remedies. It examines how governance persists when clarity is partial, when authority operates through multiple domains, and when continuity depends less on certainty than on adjustment.

If this work holds value, it will not be because it speaks from authority, but because it attends carefully to how authority functions when no position—expert or otherwise—can claim full command of the conditions it confronts.

Author’s Note

This work clarifies a confusion that appears across many political cultures: the tendency to treat “republic” and “democracy” as interchangeable ideals rather than as distinct components of governance. The chapters observe how political arrangements continue to operate when inherited categories no longer clarify what is taking place.

The method is observational. Political life is described as it is experienced: decisions made without full knowledge, terms used out of habit, and institutions that adjust internally while keeping the same outward form. The analysis begins from the limits of judgment as a daily condition: people must act before they fully understand the circumstances in which they act.

What follows does not argue for a model or defend a tradition. It traces how language, institutions, and expectations diverge across different domains of action, and how public life continues to operate under conditions that do not permit full clarity.

Chapter I

The Limits of Judgment in Public Life

*

1

Public life depends on forms of judgment that are uneven and often shaped by the pressures people face. Individuals arrive at political questions with different experiences, different levels of knowledge, and different conditions under which they weigh what is put before them. These differences do not prevent collective decisions, but they shape how clearly political terms and arrangements are perceived. Everything that follows—how authority is organized, how participation is structured, and how each is described—develops within this clarity, which is limited and variable.

2

Political terms remain stable even when they are understood to different degrees. Words such as republic and democracy have distinct meanings—one referring to an arrangement of authority, the other to a method of participation—yet are often used interchangeably. The terms carry familiarity, even when the clarity required to keep them separate varies by circumstance. As a result, public discussion may rely on established language without consistently matching it to the arrangements actually in effect.

3

A republic identifies an arrangement in which authority is held by public offices and exercised through institutions rather than personal rule. A democracy identifies the method through which people participate in public decisions, whether directly or through representation. A republic describes how authority is contained; a democracy describes how participation is organized. Because these terms refer to different dimensions of political life—one structural, the other procedural—a single system may combine both. The United States exemplifies this combination: authority is institutional and public, while participation is organized through elections and collective choice.

4

Public discussion often relies on familiar terms to describe political arrangements without tracing how authority and participation are actually organized. Broad references substitute for institutional operation, allowing language to remain continuous even as circumstances shift. The terms persist not because they precisely describe current arrangements, but because they provide a stable vocabulary through which public life can continue to be discussed as it adapts.

5

Patterns of this kind appear across many societies. When circumstances are unstable, authority tends to concentrate; when conditions are steadier, participation often widens. The direction is not uniform across countries or periods, but the pattern is recognizable: authority gathers or disperses in response to conditions rather than to the language used to describe political life. What varies is how clearly a society distinguishes between the structure that contains authority and the method through which participation occurs.

6

This movement between concentrated and dispersed authority appears differently across national contexts. In Venezuela, references to the republic have often accompanied periods of strong executive direction, while appeals to democracy have not consistently been supported by durable procedures of participation.

In the United States, the emphasis sometimes reverses. Democratic language is used to affirm broad popular involvement at the point of election, while republican structure is invoked to justify subsequent limits on participation through institutional filtering—nominee selection, confirmation timing, strategic vacancies, and procedural sequencing. Presidential nominations move from popular mandate into Senate committee review, confirmation votes, and ultimately lifetime tenure, where decision-making authority is consolidated beyond direct public reach.

The terms differ, but the underlying pattern converges: participation expands symbolically at the moment of selection and contracts structurally in the domains where authority is exercised over time.

7

Public life is easier to follow when the distinction between structure and participation remains visible. A republic identifies how authority is arranged through offices and institutions; a democracy identifies how participation is organized through collective procedures. When these terms are used without that distinction, attention shifts from institutional operation to nomenclature. Debate turns toward language rather than process, and the movement of authority becomes harder to trace.

8

No single combination of structure and participation satisfies all the demands placed on public life. Concentrated authority allows for speed but limits inclusion; broad participation expands inclusion but slows coordination. Most governments combine these elements in varying proportions, and those proportions change as conditions change. The relation between authority and participation becomes clearer in some periods and more opaque in others.

9

When this relation is unclear, people orient themselves by what is most visible. Some look to executive action; others to representative bodies; many respond primarily to immediate outcomes. These points of reference shape how the system is experienced even when its formal structure remains unchanged.

10

Public life continues not because its conditions are settled, but because decisions cannot wait for full certainty. Authority acts while circumstances remain incomplete, and participation proceeds without full anticipation of its effects. The system endures through this necessity: decisions are made under partial visibility, terms persist beyond their precision, and institutions adjust internally without losing their outward form. What holds public life together is not clarity, but the need to proceed in its absence.

Chapter II

Executive Action Under Uncertainty

1

Executive action is the domain in which decisions are least postponable. Unlike deliberative bodies, the executive is structured to act before conditions stabilize. Time pressure, incomplete information, and competing signals define its operating environment. This does not make executive judgment exceptional; it renders its limits more visible.

2

Because executive decisions are publicly observable, they often become the primary reference point through which political life is interpreted. Orders, statements, appointments, and enforcement actions are easier to see than the processes that precede or follow them. Visibility creates the impression of control even when outcomes remain uncertain.

3

The authority of the executive is often described as personal, yet it is exercised through institutional mechanisms. Decisions attributed to an individual are carried out through agencies, procedures, and delegated discretion. This layered execution allows action to proceed while responsibility is distributed across structures that remain largely out of view.

4

Periods of uncertainty tend to compress authority toward the executive. When coordination slows elsewhere, executive action fills the gap. This concentration does not require a change in constitutional structure; it occurs within existing forms as responsibilities narrow and timelines shorten.

5

Public judgment frequently focuses on decisiveness rather than conditions. Speed is mistaken for clarity; repetition for resolve. The question of whether a decision could have been otherwise is displaced by whether it was made visibly and without hesitation.

6

This focus alters how accountability is perceived. Because executive action is immediate, it absorbs praise and blame even when outcomes depend on factors beyond executive control. The executive domain becomes symbolically overloaded, functioning as a proxy for the system as a whole.

7

Over time, this dynamic reshapes expectations. Executives are asked to resolve conditions that no single office can manage. When results fall short, dissatisfaction is personalized rather than structural. Judgment narrows toward figures instead of processes.

8

The persistence of executive action under uncertainty does not indicate failure elsewhere. It reflects the necessity of action where delay carries its own costs. The executive does not eliminate uncertainty; it operates within it.

9

As established in Chapter I—The Limits of Judgment in Public Life—the distinction between structure and method remains intact. Executive authority is one structural component of the republic. Its prominence under uncertainty does not convert the system into personal rule, nor does it dissolve other forms of participation. It alters their relative visibility.

10

Executive action continues because decisions cannot wait for conditions to stabilize. What the public observes is not mastery, but motion. The domain appears decisive not because it resolves uncertainty, but because it must act while relevant information remains in flux.

Chapter III

Administrative Displacement and Procedural Substitution

1

Administrative action operates at a distance from public attention, not because it is concealed, but because it unfolds through structures designed for continuity rather than visibility. Rules are applied, procedures adjusted, and priorities reordered within agencies whose work sustains governance without occupying the foreground of political life. These actions rarely present themselves as discrete decisions, yet they shape outcomes as directly as legislative acts or executive orders.

2

Although the executive branch bears the most visible weight of action, it does not act alone. Authority moves through a dense internal structure—departments, offices, and administrative hierarchies—that translates executive direction into practice. Within this structure, different temporal orientations coexist. Some units respond to the immediacy of political mandates; others operate within constitutional and statutory frameworks intended to secure duration, stability, and institutional memory.

3

What appears publicly as a unitary executive act is, in practice, the visible edge of a distributed process. Administrative authorities do not replace the legislative function, nor do they interpret law in the judicial sense. They apply existing statutes, regulations, and precedents to concrete circumstances, exercising discretion only within bounds already defined. Governance continues through this application not because interpretation expands, but because execution must proceed even when direct legislative action is absent or delayed.

4

Procedural substitution occurs when formal decision-making cannot advance at the same pace as events. When legislation stalls, or when executive authority reaches its constitutional limits, administrative processes absorb responsibility by adjusting how existing rules are applied. Guidance is refined, enforcement priorities are reordered, and procedural pathways are recalibrated so that action can continue without altering the legal framework itself.

5

The effect of this adjustment is cumulative rather than declarative. Procedures acquire force through sustained use across cases, offices, and time. What matters is not the announcement of a decision, but the establishment of a practice that becomes operative through repetition. Authority is exercised through continuity of application, not through proclamation or display.

6

Because responsibility is distributed across agencies and routines, public judgment often struggles to locate where change occurs. Outcomes appear without a single moment of decision to which they can be traced. This dispersal does not eliminate accountability, but it complicates it. Effects are experienced before their procedural origins are understood, if they are understood at all.

7

Over time, this mode of governance reshapes public expectations. Citizens may sense that conditions have shifted while remaining uncertain about who acted or how. Dissatisfaction attaches to the system as a whole rather than to identifiable actors, not because authority is absent, but because it operates through channels that do not align with public narratives of decision and responsibility.

8

Administrative displacement does not signal institutional breakdown. It reflects the necessity of maintaining governance under constraint. When formal decisions cannot be taken at the speed required, procedures adapt so that authority continues to function without exceeding its legal bounds. The system does not suspend itself; it adjusts its pathways.

9

This domain illustrates the separation between form and operation established in the opening chapter. The constitutional structure of authority remains intact, while its execution shifts in emphasis and sequence. What changes is not who holds power, but how that power is carried forward under conditions that do not permit explicit resolution.

10

Governance persists through these substitutions because action cannot stop. Authority moves not by abandoning its limits, but by working within them. The continuity of public life depends less on visible decisions than on the capacity of institutions to apply existing frameworks to changing circumstances—imperfectly, and without claiming finality.

Chapter IV

Electoral Ritual and the Persistence of Form

1

Elections are the most recognizable feature of democratic participation. They provide a recurring structure through which public involvement is organized and displayed. Their regularity creates a sense of continuity even as surrounding conditions change.

2

As ritual, elections affirm participation through repetition. Procedures remain familiar—campaigns, voting, certification, transition—and establish a shared sequence that signals order and legitimacy. These outward forms sustain confidence in the process, even when outcomes remain uncertain.

3

Elections endure not because they resolve conflict, but because they organize trust at the point of selection. They do not settle disagreement; they make continued coordination possible by establishing a recognized moment of authorization.

4

Once trust is organized at the point of selection, public attention shifts from the mechanics of participation to the visibility of results. Winning and losing replace examination of how participation translates into policy, administration, or enforcement. The ritual satisfies the expectation of involvement, while attention moves away from the pathways through which authority is exercised after selection.

5

This emphasis on outcome reinforces symbolic stability. As long as elections occur on schedule and results are recognized, the system appears intact. Questions about how decisions are made afterward—how authority is carried forward, distributed, and constrained—receive less sustained attention.

6

Discrepancies between electoral choice and lived experience are often attributed to individuals rather than to institutional pathways. Dissatisfaction becomes personalized, while the structural distance between participation and governance remains largely unexamined.

7

Electoral rituals persist because they serve a stabilizing function. They mark transitions, renew legitimacy, and provide a shared reference point for public life. Their endurance does not depend on their capacity to resolve underlying pressures, but on their ability to preserve coordination in the presence of disagreement.

8

As conditions change, participation may become more expressive than effective. Voting signals presence and alignment, even when it does not materially alter administrative or executive trajectories. Expression remains visible; influence becomes less certain.

9

Democracy, understood as method, remains visible and active. What fluctuates is the degree to which participation reaches into the domains where decisions are continuously adjusted, and where authority continues to operate after the moment of voting.

10

Public life continues through this arrangement because action cannot pause at the point of selection. Decisions proceed while conditions evolve, information accumulates unevenly, and responsibility shifts across domains. What endures is not resolution, but continuity: governance advances through adjustment rather than completion, sustained by institutions that act without claiming finality.