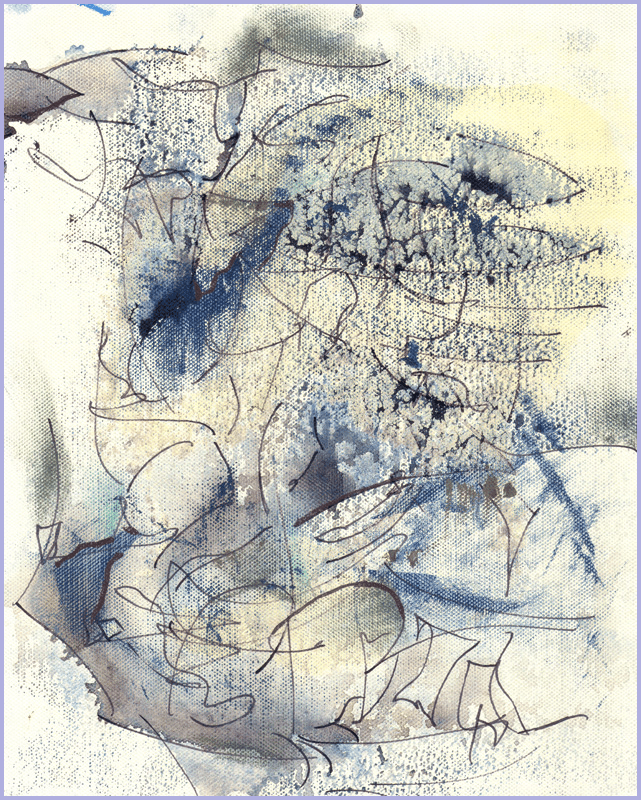

“Echoes of a life devoted to the elusive”

*

*

In memoriam José Luis Montero

For him, inspiration didn’t strike—it settled. It arrived not with answers, but with permission to begin.

There was no ritual. No dramatic turning point. Only the canvas, the scent of oil, the shifting light across the floor. One day folding into the next, until the work became its own weather—sometimes clear, sometimes stormy, but always present.

He believed in attention, not mastery.

What moved him wasn’t how the painting was achieved at any given moment, but when deconstructed he had to reclaim it, not out of skill, but out of necessity—when the hand moved before thought, and something more honest than intention began to lead. And when it happened, it asked everything of him.

Any one watching—anyone but him—would have seen very little. A trace. A pause. A slight adjustment. But inside, something in him was listening—not to himself, but to the world, the material, the echo of a form not yet known.

He didn’t make work to be remembered, though he carried each piece like a child of his. He made it to stay alive. And when he encountered a finished painting years later, it stirred him physically. It wasn’t nostalgia. It was the smell of pigment, the sound of bristles, the grief of something nearly realized—lost, then found again.

Some days, the work moved with a kind of ease. Other days, it refused. He learned not to chase either.

He always began without knowing what he was after. A shade. A flicker of transparency. A stroke that unsettled the surface. Often the brush would stop midair, suspended while he waited for the next move to reveal itself. Sometimes nothing came. Those pieces sat untouched for weeks—a quiet unease in the corner of the room.

He lived alongside their silence.

The studio was never clean, but always ordered. Rags folded. Jars fogged with old turpentine. Walls bearing soft outlines of past canvases. The mess wasn’t careless. It was lived-in—not careless, just lived-in. Notes of Goethe’s pyramidal harmony hung besides mineral samples, sketches, color wheels, torn letters from art dealers. Not for revelation—but for proximity.

Not every piece held. Some failed completely. Others, losing urgency layer by layer, failed gradually, He kept those too—not as records, but as reminders. Where the hand had gone quiet. Where the work had ceased to ask. Yet they became platforms—spaces for later returns, for deeper entry.

His days had no fixed schedule, though a rhythm formed over the years—a long devotion, interrupted, resumed, endured.

Now, he arrived late morning from the City. The studio held the faint scent of wax and turpentine, laced with something older—dust, fabric, memory. He opened a window if weather allowed. Not for light but for air. For movement. For the slow turning of the fans like breath.

He made tea. Sometimes he played Bach, or a pianist, whose fingers pressed deeper into the keys than others. Other mornings: National Public Radio. A poet, a scientist, someone trying to say the impossible in ordinary words. He liked the trying more than the saying.

He painted standing—rarely seated. Some days he moved constantly between easel, sink, and mixing table. Other days he barely moved at all. Just watched.

Lunch was simple. Bread. Fruit. A little cheese. Sometimes eggs, lentils, soup across several days. He didn’t eat out much—not out principle, but because it broke the thread.

If tired, he would lie on the couch at the back wall. Twenty, thirty minutes. No more. And when he woke, the light had shifted again—slanted, softened, more forgiving. The canvas looked changed. As if it had waited for his absence.

Late afternoons were often the best. A second wind, free of pressure. There was a looseness in the air, born from knowing no one would knock or call. He spoke to the work then—not aloud, but inwardly. This tint? Too warm. This stroke? Too sure. Let it break. Let it breathe. Let it speak without saying.

Sometimes the medium resisted. A brush faltered. A gesture collapsed. He didn’t fight. He gave it space. If he stayed patient, it found its rhythm again.

Not everything reached completion. Some works remained open—not abandoned, simply finished enough. Others came suddenly, like music that plays without lifting the fingers.

By evening, he cleaned his tools. Never rushed. He wiped the palette. Rinsed the jars. Hung the rags to dry. It was a kind of thanks. Not to the painting. To the day.

Then lights out. Door closed. Nothing declared. Nothing completed. Yet something always moved forward.

Grief, too, remained. It lived in the room like dust—settled in corners, clinging to stretchers still bare, woven into old white sheets.

His sister’s illness came slowly, then all at once—while Adagio in G Minor played low across the studio. He painted through it. Not to escape, but because stopping would have undone him. In the silence between strokes, he could feel her breath weakening. Sometimes he imagined she could see the work from wherever she was. That each finished piece carried a word he hadn’t dared to say aloud. She would have understood. She always had.

Later, when his former lover died—alone, unexpectedly, in Berlin—he stopped painting altogether. The studio felt still in a way he couldn’t enter. Even the canvas turned away from him. When he returned, it was with a muted palette. Dry. Indifferent. The first brush stroke broke in two. He left it. And continued.

Desire, too, had quieted. Not vanished. Just softened. In youth it had been urgent, irrepressible. Now it hovered—an echo that came and went. He didn’t shame it or perform it. He lived beside it, the way one lives beside a field once burned, now slowly greening.

Grief didn’t interrupt the work. It deepened it. Not in theme—but in texture. Some of those paintings seemed familiar to others. But he knew what they held—the weight of holding steady while coming apart inside.

Even now, some colors recalled a bedside. A winter walk. The sound of someone no longer breathing. A flat grey. A blue once brilliant, now tempered between longing and restraint.

He wondered sometimes about that tension.

But when he painted, stillness returned.

Seventeen years ago, when chemotherapy ended, the days grew quieter.

There was no triumph. Just a slow return to rhythm—different now. The body had changed. So had the mind. He couldn’t paint for hours without fatigue. The gestures once fluid were heavier, more tentative.

He didn’t resist it.

The studio remained, but the center of gravity shifted. Where once he reached for a brush, now he reached for a pen. At first, just notes. Fragments. A way to hold the day together. Then came sentences. Paragraphs. Not about himself, not directly. About time. Memory. Presence. Writing became a solace. A way to shape what the body could no longer carry. A place to move, still, with care.

It wasn’t the end of painting. Just a pause. A migration. Writing required its own attention, its own patience. And he recognized in that a familiar devotion.

Sometimes, the canvas still called. It would rest untouched for weeks. Then one day, without announcement, he would begin again.

The two practices lived side by side. Some days the brush. Some days the page. No hierarchy. No regret. Only the quiet persistence of a life still unfolding.

There is no final piece. No last word.

He understands now: a life is not made of things finished, but of gestures continued—marks made in good faith, even when no one is watching. A sentence begun. A color mixed. A canvas turned to the wall—not in shame, but because it had said enough.

He no longer asks what comes next. That question no longer troubles him.

If anything remains, it will not be the name, or the archive, or even the objects themselves. It will be the integrity of attention—the way he returned, again and again, to meet the moment as it was.

Not to make something lasting.

But to live, briefly, in truth.

*

Ricardo F Morin Tortolero

Bala Cynwyd, Pa., June 14, 2025

Editor: Billy Bussell Thompson

Author’s Note

This piece, like much of what I’ve made in recent years, exists because of those who have sustained me.

To David Lowenberger—whose love and steadfastness give my life its rhythm. Without him, continuity itself would falter.

To José Luis Montero, my first art teacher, whose presence early on became a compass I’ve never stopped following.

To my parents, whose quiet influence shaped my regard for form, devotion, and care.

And always, to my friend and editor, Billy Bussell Thompson, whose voice lives quietly in mine.