… Power, Storytelling, and the Fear of Losing Significance“

By Ricardo Morin, July 2025

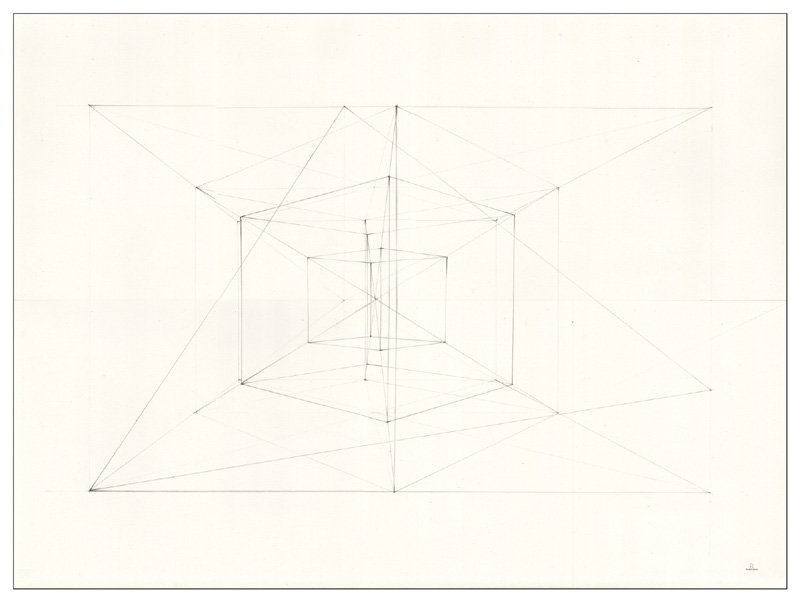

The Stilobato of Zeus Underwater

CGI

2003

Abstract

This essay examines the human mind’s compulsion to invent stories—not merely to understand reality, but to replace it. It explores how narrative becomes a refuge from the void, a form of self-authorship that seeks both meaning and control. The tension between rational observation and imaginative projection is not a flaw in human reason, but a clue to our instability: we invent to matter, to belong, and to assert that we are more than we fear we might be. At its core, this is a reflection on the seductive authority of story—the way it offers not just identity but grandeur, not just comfort but a fragile illusion of power. Beneath every myth may lie the terror of nothingness—and the quiet hope that imagination might rescue us from the fear of a diminished understanding of our own importance.

.

The Delusion of Authority: Power, Storytelling, and the Fear of Losing Significance

We tell stories to make sense of life. That much seems obvious. But if we look a little deeper, we may find that the stories we tell—about ourselves, our beliefs, our traditions, even our suffering—aren’t just about sense-making. They’re about power. Not always power over others, but something more private and often more dangerous: the power to feel central, secure, and superior in a world that rarely offers those guarantees.

This need shows up in ways that often appear noble: tradition, loyalty, virtue, cultural pride, spiritual clarity. But beneath many of these lies a hunger to be more than we are. To matter more than we fear we do. To fix the feeling that we are not quite enough on our own.

We don’t like to think of this as a thirst for power. It sounds selfish. But in its quieter form, it’s not selfishness—it’s survival. It’s the need to look in the mirror and see someone real. To look at the world and feel part of a story that means something. And when we don’t feel that, we make one up.

Sometimes it takes the shape of tradition: the rituals, the mottos, the flags. These things give us the illusion that we are part of something lasting, something sacred. But often, what they really do is offer us borrowed certainty. We repeat what others have repeated before us, and in that repetition we feel safe. We mistake performance for truth. This is how belonging becomes obedience—and how ritual becomes a mask that hides the absence of real thought.

Sometimes it takes the shape of insight. We adopt the language of spiritual clarity or mystical knowing. We speak in riddles, or listen to those who do. But often, this too is about authority: the idea that we can bypass doubt and land in a place of higher understanding. When we hear phrases such as “listen with all your being,” or “intellectual understanding isn’t real understanding,” we are being invited to give up reason in exchange for what feels like truth. But the feeling of truth is not the same as the hard work of clarity.

And sometimes, this hunger for centrality shows up in identity. We claim pain, pride, or history as a kind of moral capital. We say “my people” as if that phrase explains everything. And maybe sometimes it does. But when identity becomes a shield against criticism or a weapon against others, it stops being about belonging and starts being about authority—about who gets to speak, who gets to be right, who gets to be seen.

Even reason itself is not immune. We use logic, not only to understand, but to protect ourselves from uncertainty. We argue not only to clarify, but also to win. And slowly, without noticing, we turn the pursuit of truth into a performance of control.

All of this is understandable. The world is confusing. The self is fragile. And deep down, most of us are terrified of being insignificant. We fear being one more nameless voice in the crowd. One more moment in time. One more life that ends and disappears.

So we reach for authority. If we can’t control life, maybe we can control meaning. If we can’t escape time, maybe we can tell a story that lasts. But this, too, is a delusion—one that leads to suffering, to isolation, and to conflict.

Because when everyone is the center of their own story, when every group insists on its own truth, when every insight claims to stand above question—no one listens. No one changes. And no one grows.

But what if we gave up the need to be right, to be central, to be superior?

What if we didn’t need to be grand in order to be real?

What if we could tell stories not to control reality, but to share it?

That would require something more difficult than intelligence. It would require humility. The willingness to be small. To be uncertain. To live without authority and still live meaningfully.

This isn’t easy. Everything in us pushes against it. But perhaps this is the only path that leads us out of performance and into presence. Out of delusion and into clarity. Not the clarity of slogans or doctrine, but the clarity of attention—of seeing without needing to rule over what is seen.

We don’t need to be gods. We don’t need to be heroes. We just need to be human—and to stop pretending that being human isn’t already enough.

*

Annotated Bibliography

- Arendt, Hannah: The Origins of Totalitarianism. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1951. (A foundational study on how ideological certainty and group identity can undermine thought, clearing the way for emotional conformity and mass control.)

- Beard, Mary: Twelve Caesars: Images of Power from the Ancient World to the Modern. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2021. (Explores how images and stories of rulers are crafted to sustain the illusion of divine or inherited authority.)

- Frankl, Viktor E.: Man’s Search for Meaning. Boston: Beacon Press, 2006. (Reflects on the will to meaning as a basic human drive, particularly under extreme suffering, showing how narrative can sustain dignity and life.)

- Kermode, Frank: The Sense of an Ending: Studies in the Theory of Fiction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967. (Examines how people impose beginnings, middles, and ends on chaotic experience, seeking structure through storytelling.)

- Nietzsche, Friedrich: On the Genealogy of Morality. Translated by Carol Diethe. Edited by Keith Ansell-Pearson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007. (Argues that moral systems often arise from resentment and masked power struggles rather than pure virtue or reason.)

- Oakeshott, Michael: Rationalism in Politics and Other Essays. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1991. (Critiques the rationalist impulse to systematize human life, warning against overconfidence in reason’s ability to master reality.)

- Todorov, Tzvetan: Facing the Extreme: Moral Life in the Concentration Camps. Translated by Arthur Denner and Abigail Pollack. New York: Metropolitan Books, 1996. (Offers insight into how identity and morality hold—or collapse—under conditions that strip away illusion, highlighting the limits of narrative.)

- Wallace, David Foster: This Is Water: Some Thoughts, Delivered on a Significant Occasion, about Living a Compassionate Life. New York: Little, Brown, 2009. (A short meditation on how default thinking shapes our perception and how awareness—not authority—offers a path to freedom.)