*

*

To my parents

*

Acknowledgements

~

I wish to acknowledge Billy Bussell Thompson for his meticulous editorial guidance. His feedback sharpened the structure, precision, and internal discipline of this work.

Preface

“Unmasking Disappointment” follows a line of inquiry present throughout my work: the examination of identity, memory, and the relations that emerge when life unfolds across cultural boundaries. Although I have lived outside Venezuela for more than five decades and became a naturalized citizen of the United States twenty-four years ago, my relationship to the country of my birth remains a persistent point of reference. The distance between these conditions—belonging and removal—forms the backdrop against which this narrative takes shape.

This work belongs to a broader autobiographical project that gathers experiences, observations, and questions accumulated over time. While personal in origin, it does not proceed as confession or memoir. Its method is sequential rather than expressive: individual exposure is situated within historical forces and political structures that have shaped Venezuelan life across generations. The intention is not to reconcile these tensions, but to render them visible through recurrence, record, and consequence.

“Series I” introduces the first thematic clusters of this inquiry. The episodes assembled here do not advance a single thesis, nor do they aim at resolution. They trace points of friction where private experience intersects with public power, and where political narratives exert pressure on ordinary life. Across these encounters, patterns emerge—not as abstractions, but as conditions that alter how authority is exercised, how responsibility is displaced, and how agency is constrained.

The chapters that follow examine the pressures produced by systemic inequality and trace contemporary Venezuelan conditions back to their historical formation. Autocratic rule and popular consent appear not as opposing forces, but as elements that increasingly entangle and weaken one another. Within this entanglement, truth does not disappear; it becomes less evenly accessible and more readily displaced by narrative.

When public discourse is shaped by propaganda and misinformation, authoritarian structures gain resilience. Recovering truth under such conditions does not resolve political conflict, but it clarifies the limits within which political life operates. Agency emerges not as an ideal, but as a condition sustained—or undermined—through practice and consequence.

This work does not propose deterministic explanations or simple remedies. It proceeds by accumulation, drawing attention to patterns that persist despite changing circumstances. What it asks of the reader is not agreement, but attention: to evidence, to sequence, and to the conditions under which political freedom may be meaningfully exercised.

Writing from Bala Cynwyd, Pennsylvania, and Fort Lauderdale, Florida, I remain aware of the distance between the environments in which this work is composed and the conditions it examines. That distance does not confer authority; it imposes responsibility.

Ricardo Federico Morín

Bala Cynwyd, Pennsylvania, January 21, 2025

*

Table of Contents

*

- Chapter I – A Written Language.

- Chapter II – Our Recklessness.

- Chapter III – Point of View.

- Chapter IV – A Dialogue.

- Chapter V – Abstract.

- Chapter VI – Chronicles of Hugo Chávez (§§ I-XVII).

- Chapter VII – The Allegorical Mode.

- Chapter VIII – The Ideal Government and the Power of Virtue.

- Chapter IX – The First Sign: On Political and Social Resentment.

- Chapter X – The Second Sign: The Solid Pillar of Power: The Military Forces.

- Chapter XI – The Third Sign: The Asymmetry of Political Parties.

- Chapter XII – The Fourth Sign: Autocracy (§§ 1-9): Venezuela (§§ 10-23), The Asymmetry of Sanctions (§§ 24-32).

- Chapter XIII – The Fifth Sign: The Pawned Republic.

- Chapter XIV – The First Issue: Partisanship, Non-partisanship, and Antipartisanship.

- Chapter XV – The Second Issue: On Partial Truths and Repressive Anarchy.

- Chapter XVI – The Third Issue: The Clarion of Democracy.

- Chapter XVII – The Fourth Issue: On Human Rights.

- Chapter XVIII – The Fifth Issue: On the Nature of Violence.

- Chapter XIX – The Ultimate Issue: About the Deliverance of Injustice.

- Acknowledgments.

- Epilogue.

- PostScript.

- Appendix: Author’s Note, Prefatory Note. A). Venezuelan Constitutions [1811-1999], Branches, and Departments of Government. B) Evolution of Political Parties: 1840-2024. C) Laws Enacted by the Asamblea Nacional. D) Clarificatory Note on Domestic Coercion, Foreign Presence, and Intervention.

- Bibliography.

~

*

Chapter I

*

A Written Language

~

Stability is often sought where it cannot be secured. Experience has shown this repeatedly. Even careful intentions tend to draw one into uncertain terrain, where understanding lags behind consequence. At the desk, as late-afternoon light reaches the page, writing assumes a practical function: it becomes a means of ordering what would otherwise remain unsettled. The act does not resolve vulnerability, but it records it. Whether time alters such conditions remains uncertain; what can be done is to give them form.

What follows moves from the conditions of writing to the conditions it must confront.

*

Chapter II

*

Our Recklessness

~

“Our painful struggle to deal with the politics of climate change is surely also a product of the strange standoff between science and political thinking.” — Hannah Arendt: The Human Condition: Being and Time [1958], Kindle Book, 159.

*

1

The COVID pandemic and the 2023 Canadian wildfires, among other recent events, have made visible conditions that were already in place. These events did not introduce new vulnerabilities as much as they revealed the extent to which existing systems depend on economic incentives and political habits that privilege extraction over preservation. During the period when smoke from the fires reached the northeastern United States, daylight in parts of Pennsylvania was visibly altered and registered the reach of events unfolding at a considerable distance. Such occurrences do not stand apart from prevailing economic arrangements; they coincide with a model that treats natural conditions as commodities and absorbs their degradation as an external cost.

2

The fires in California in 2025, like those that spread across Canada in 2023, do not present themselves as isolated occurrences. They form part of a sequence shaped by environmental neglect, political inertia, and sustained industrial expansion. Conditions such as desertification, resource scarcity, and population displacement no longer appear solely as projected outcomes; they are increasingly registered as present circumstances. Scientific assessments indicate that these patterns are likely to intensify in the absence of structural change. [1][2][3] What is brought into view, over time, is not a singular failure but a system that continues to operate according to priorities that favor immediate yield over long-term continuity.

3

The question of balance does not arise solely as a technical problem. It emerges within a moral and political field shaped by prevailing economic assumptions. The treatment of nature—and more recently of artificial intelligence—as a commodity reflects a trajectory in which matters of shared survival are increasingly translated into market terms. Under such conditions, considerations that once belonged to collective responsibility are recast as variables within systems of calculation.

4

Such patterns place increasing strain on conditions necessary for collective survival. Responses to these conditions vary and range from indifference to urgency, though urgency does not invariably produce clarity. What becomes apparent, across repeated instances, is a tendency for crisis to recur without sustained adjustment. This recurrence parallels the political histories examined in the chapters that follow, where warning and consequence frequently fail to align.

Endnotes—Chapter II

- [1] Derek P. Tittensor, et al, “Integrating climate adaptation and biodiversity conservation in the global ocean” (Science Advances: 27 Nov 2019), Vol 5, Issue 11 DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aay9969: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.aay9969

- [2] “Hugo Graeme, “Migration, Development and Environment”, № 35 (Geneva: International Organization for Migration [IOM] November 2008): https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/mrs_35_1.pdf

- [3] World Bank Group, “Climate Change Could Force 216 Million People to Migrate Within Their Own Countries by 2050” (Washington: World Bank Group, September 13, 2021): https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2021/09/13/climate-change-could-force-216-million-people-to-migrate-within-their-own-countries-by-2050

*

Chapter III

Point of View

1

Conversations with my editor, Billy Bussell Thompson, have accompanied the development of this work over time. His attention to research method and to the structure of argument has contributed to the clarification of its scope and direction. These exchanges, often conducted at a distance and without ceremony, formed part of the process through which the present narrative took shape. After an extended period of uncertainty regarding how to approach the subject of Hugo Chávez, the contours of Unmasking Disappointment gradually emerged.

2

Hugo Chávez entered national political life as a leader whose authority was exercised in opposition to political liberalism. [1] While his public discourse emphasized alignment with the poor, the material benefits of power accumulated within a narrow circle. [2] Over the course of his tenure, democratic institutions in Venezuela experienced progressive weakening, and governance assumed increasingly authoritarian forms. These developments become more legible when situated within the historical record and examined through documented practice rather than rhetorical claim.

3

The events that followed Chávez’s rule are marked by disorder and unresolved consequence. Their persistence draws attention to questions of historical accountability and collective responsibility that remain unsettled. Examining the record of autocratic leadership—its ambitions as well as its failures—provides a means of approaching the problem of justice in Venezuela without presuming resolution. Through this examination, enduring tensions come into view as conditions to be understood rather than conclusions to be reached.

~

Endnotes—Chapter III

- [1] The term caudillo originates in Spanish and has historically been used to describe a leader who exercises concentrated political and military authority. In the Venezuelan context, the term carries particular resonance and refers to figures associated with the post-independence period of the nineteenth century. Such leaders tended to consolidate power through a combination of personal authority, allegiance from armed factions, and the promise—whether substantive or rhetorical—of maintaining order under conditions of instability. While some were regarded as defenders of local or national causes, others became associated with practices that facilitated authoritarian governance and weakened institutional structures. The concept of the caudillo continues to function within Venezuelan political culture as a descriptive category applied to leadership forms that combine popular support with concentrated power.

- [2] Nicholas Casey, “Jet, Horses and Bribes: How a Venezuelan Official Became a Billionaire” (New York Times, Nov. 23, 2018): https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/23/world/americas/venezuela-andrade-corruption-bribes.html; Vanessa Buschschlüter, “Venezuela corruption: Hugo Chávez’s nurse guilty of money laundering” (BBC, December 14, 2022): https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-63971269; Pete D’Amato, “Being the ex-President’s daughter pays off: Hugo Chavez’s ambassador daughter is Venezuela’s richest woman” (Miami Daily Mail, August 10, 2015): https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3192933/Hugo-Chavez-s-ambassador-daughter-Venezuela-s-richest-woman-according-new-report.html; U.S. Attorney’s Office, Southern District of New York, “Former Venezuelan Official Hugo Armando Carvajal Barrios Extradited To The United States On Narco-Terrorism, Firearms, And Drug Trafficking Charges” (July 19, 2023): https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdny/pr/former-venezuelan-official-hugo-armando-carvajal-barrios-extradited-united-states; Brian Ellsworth and Mayela Armas, “Special Report: Why the military still stands by Venezuela’s beleaguered president” (Reuters: June 28, 2019): https://www.reuters.com/article/us-venezuela-military-specialreport/special-report-why-the-military-still-stands-by-venezuelas-beleaguered-president-idUSKCN1TT1O4/

*

Chapter IV

*

A Dialogue

*

A series of conversations between BBT and the author accompanied the examination of Venezuelan politics and history developed in this section. These exchanges formed a transitional space in which reflection gave way to historical inquiry, allowing questions of interpretation, responsibility, and record to be addressed through dialogue rather than exposition.

1

—RFM: “My writing has been concerned with the evolution of Venezuela’s political landscape, with particular attention to the emergence of authoritarian forms of rule. The focus has been less on abstract doctrine than on how specific policies translated into everyday conditions for ordinary Venezuelans.”

2

—BBT: “Examining how authoritarian leadership shapes political conditions is necessary, though the term itself is often contested and applied unevenly. In Chávez’s case, the use of propaganda was not exceptional in form, but it was consistently employed as an instrument of governance. How did official narratives during his tenure circulate, and what effects did they have on public perception over time?”

3

—RFM: “Propaganda is not unique to Chávez; it functions as a recurring instrument across political systems. In Venezuela, official media regularly attributed economic hardship to external interference rather than to domestic policy decisions. At the same time, material conditions deteriorated, with shortages emerging from economic mismanagement and later compounded by external restrictions. Opposition groups also circulated counter-narratives, which in turn elicited responses from the State. These exchanges unfolded within a historical context shaped by civil conflict and Cold War alignments, and produced a fragmented informational environment. Within that environment, responsibility for economic decline was frequently displaced, while public perception was managed through repetition rather than resolution. The social and economic reforms invoked in justification did not, over time, yield the reductions in poverty and inequality that had been promised.”

4

—BBT: “To render Venezuela’s political conditions with some accuracy, attention must be given to how ordinary citizens encountered these dynamics in daily life. How were such conditions navigated in practice, particularly where political discourse intersected with immediate economic necessity?”

5

—RFM: “The economic collapse that followed the decline of the oil-based model intensified poverty and placed sustained pressure on public services. Examined in sequence, this period shows how colonial legacies and authoritarian practices converged in the formation of Chavismo. Episodes such as the 1989 riots known as El Caracazo registered widespread disaffection with established parties and democratic institutions. Under such conditions, the demands of securing basic necessities frequently outweighed engagement with abstract political principles.”

6

—BBT: “Clarity in narrative depends in part on recognizing the assumptions that guide interpretation. When these assumptions are made explicit and examined, the account becomes less directive and more accessible, allowing readers to follow the record without being steered toward a predetermined position.”

7

—RFM: “No narrative proceeds without interpretation, including this one. Writing provides a means of approaching Venezuela’s history—its colonial formation, episodes of authoritarian rule, and periods of political disruption—without foreclosing alternative readings. A coherent account need not be exhaustive; it remains open insofar as it attends to implication and consequence rather than resolution.”

8

—BBT: “The exchange itself underscores the importance of careful narration when approaching Venezuela’s political and social record. Attending to multiple viewpoints does not resolve complexity, but it allows a more coherent account to emerge without reducing that history to a single explanatory frame.”

The exchange marked a transition from reflective inquiry to historical record.

~

*

Chapter V

*

Abstract

*

1

This section examines the sequence through which the political project articulated under Hugo Chávez assumed autocratic form. Rather than attributing this outcome to a single cause, the inquiry proceeds by tracing how leadership decisions unfolded within a convergence of historical conditions, institutional arrangements, economic pressures, and geopolitical alignments. The account does not begin from conclusion, but from record.

2

Attention remains on how authority was exercised and how its effects registered within Venezuelan society. Historical circumstance, institutional design, and external influence are examined not to simplify the record, but to make visible the interdependencies through which power consolidated over time. What emerges is not an explanatory thesis, but a configuration whose coherence can be assessed only through sustained attention to sequence and consequence.

~

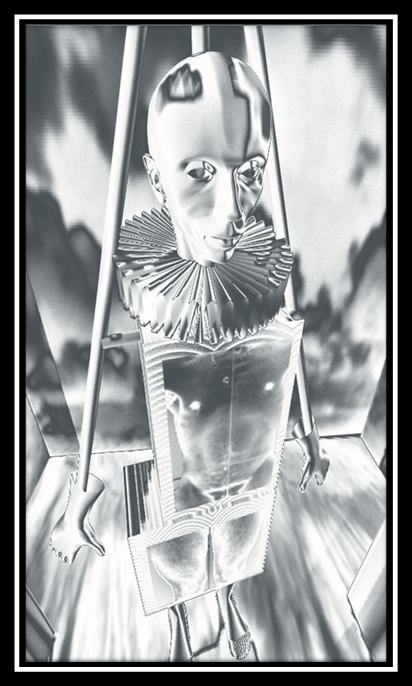

![This image has an empty alt attribute; its file name is 0005.jpg

Decantation [2003], CGI by Ricardo Morín](https://observationsonthenatureofperception.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/0005.jpg?w=533)