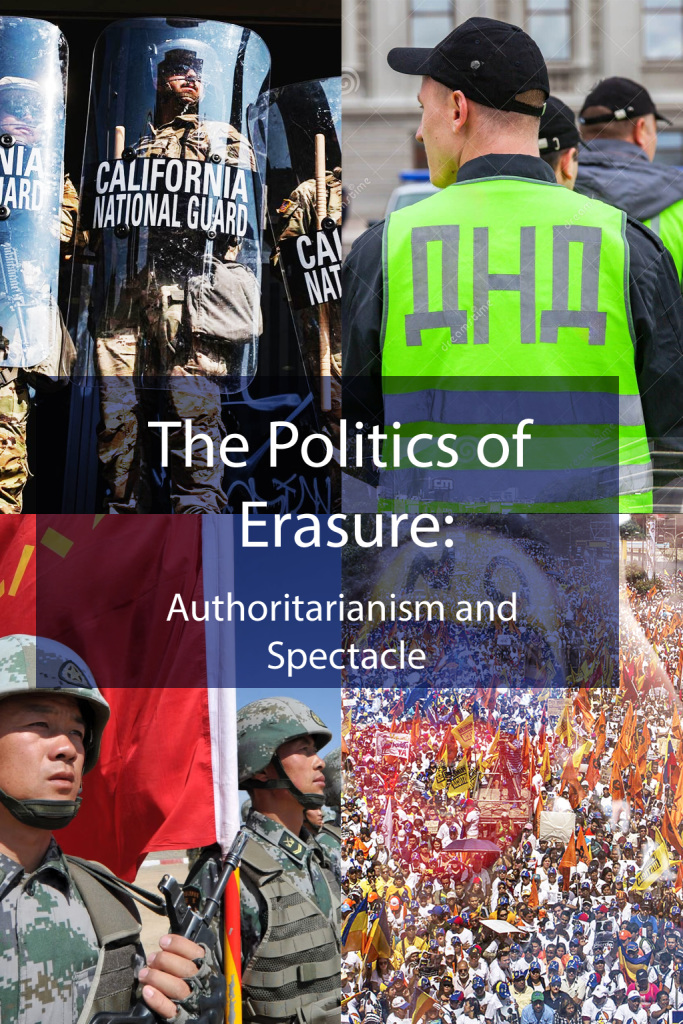

Resentment, Force, and the Architecture of Power

*

*

Ricardo F. Morín

Oakland Park, F.

December 12, 2025

Author’s Note:

The preceding chapters established a standard by which political life may be assessed. They did not propose an ideal government as a program, nor did they advance virtue as a moral aspiration detached from circumstance. They articulated, instead, a set of constraints—justice, restraint, and judgment—without which governance loses proportion and language loses meaning.

The chapters that follow examine how those constraints were displaced. They do not proceed from intention or ideology, but from accumulation. Political resentment, once mobilized as a source of legitimacy, became a governing instrument rather than a condition to be addressed. Military authority, long embedded in Venezuela’s institutional history, ceased to function as a stabilizing force and assumed a constitutive role in political identity. Party structures, rather than mediating between society and the State, hardened into asymmetries that neutralized opposition and converted pluralism into fragmentation.

These developments did not arise in isolation, nor were they the product of a single figure or moment. They emerged through a convergence of affect, coercion, and institutional design. The disappointment examined here is not emotional in nature. It is structural: a consequence of ideals retained as symbols after their operative limits had been removed.

“Part II” traces these mechanisms in sequence. What appears is not a rupture from the ethical geometry outlined earlier, but its progressive distortion. Virtue persists in language while constraint disappears in practice. Governance continues to speak in universal terms even as power concentrates and accountability dissolves. The result is not merely authoritarianism, but a political order in which disappointment becomes systemic—produced, sustained, and normalized.

*

Chapter IX

~

The First Sign

*

On Political and Social Resentment

1

From the ashes of Venezuela’s fractured democracy arose a bitter sentiment: a resentment that reshaped the political and social fabric of the nation. Political and social resentment, born of inequality, historical grievances, and unfulfilled promises, became the primary currency of Hugo Chávez’s rhetoric and policies. This undercurrent of discontent allowed Chávez to rally the dispossessed under the banner of his Bolivarian Revolution, which reframed a nation’s despair as the foundation of his movement.

2

Chávez’s speeches evoked the memories of colonial exploitation and 20th-century corruption; they cast the elite as Venezuela’s oppressors. The enduring inequality between rural and urban areas, the oil-rich elite, and impoverished communities was central to this narrative. Through fiery oratory, Chávez positioned himself as the voice of the marginalized, promising economic justice and empowerment. [1]

3

Yet, behind the veneer of inclusion and equity lay policies that ultimately betrayed these ideals. The social programs known as Misiones, though impactful in the short term, were not sustainable. Funded by volatile oil revenues, these initiatives addressed symptoms rather than structural causes and ultimately deepened Venezuela’s dependency on oil wealth and the state’s centralized control. [2]

4

Despite their initial popularity, these policies created new inequalities. Access to state benefits became contingent on political loyalty and fostered division and mistrust among the very populations Chávez had vowed to uplift. Corruption and inefficiency plagued these programs, leaving many promises unfulfilled and further polarized Venezuelan society.

5

The Cult of Personality

*

Chávez’s charisma played a critical role in channeling resentment into political capital. His larger-than-life persona blurred the boundary between leader and nation; he transformed dissent into perceived betrayal of patriotism. This cult of personality, portraying critics as enemies of progress, allowed him to centralize power with little resistance.

6

As Chapter VI, Chronicles of Hugo Chávez, demonstrated, Chávez presented himself as the champion of the people, while his approach undermined pluralism and fostered a climate of fear and conformity. This dynamic cemented his control but weakened democratic institutions. His frequent invocation of historical grievances acted as a smokescreen for growing authoritarianism.

7

Exploiting Division

*

The Bolivarian Revolution thrived on cultural division, deliberately stoking class, racial, and regional tensions to consolidate power. Amplifying resentment and ensuring loyalty among his base, Chávez’s rhetoric of “us versus them” weaponized existing fractures in Venezuelan society. By cultivating distrust, his regime inhibited collective action across class or political lines and fractured the potential for broad-based scrutiny by a legitimate opposition.

8

This strategy also extended to the private sector. Expropriations, price controls, and the vilification of business leaders dismantled private enterprise and reinforced dependence on the State. These actions exacerbated economic decline, displaced blame onto perceived enemies of the revolution, and perpetuated cycles of resentment. [3]

9

Its Allure

*

Chávez’s manipulation of resentment was not simply a response to inequality but an exploitation of it. By harnessing historical and contemporary grievances, he galvanized a movement that promised to heal Venezuela’s wounds while simultaneously deepening its divisions. The promise of unity and progress became a pretext for authoritarianism; it left behind a legacy of mistrust, unmet expectations, and fractured institutions.[4]

10

When resentment is allowed to govern a nation, it may consume the very structures meant to protect it. Although Chávez offered hope to the disillusioned, his revolution ultimately amplified the very injustices it claimed to address.

~

Endnotes—Chapter IX

- [1] Luis Vicente León, Chávez: La Revolución No Será Televisada (Caracas: Editorial Planeta, 2008) 112-127.

- [2] Luis Vicente León, Misiones Sociales: Un Gobierno de Dependencia? (Caracas: Editorial Alfa, 2011) 45-59.

- [3] Michael F. A. Sargeant, The Venezuelan Military Under Chávez: Political Influence and Militarization (New York: Columbia University Press, 2013) 150-165.

- [4] Gustavo Coronel, Venezuela: The Collapse of a Democracy (Miami: Editorial Santillana, 2015) 203-220.

~

*

Chapter X

*

The Second Sign

~

The Solid Pillar of Power: The Military Force

1

The dynamics outlined in earlier chapters reveal how the military functioned not merely as an institution but as an axis of political identity. Military rule has shaped Venezuela’s identity since its independence in 1811—see Appendix: 19th and 20th-century Constitutions. This endurance stems not only from political necessity but from a deeply ingrained belief in military dominance—a force that has long stifled Venezuela’s progress. For nearly two centuries, from the early republic to the present, the military has been the backbone of Venezuela’s governance, shaped by a succession of caudillos—each with distinct ambitions yet bound by reliance on military authority. Long cast as the steady hand in political turbulence, the military remains a rigid scaffold encasing Venezuela’s political landscape. Chávez’s rise and his reconfiguration of military influence must be understood within this context. As his predecessors had done, Chávez sought to harness military power within a new vision of State control and to intertwine military and political authority in ways that reinforced Venezuela’s autocratic rule.

2

In the wake of independence, Venezuela grappled with instability as military leaders—at times disciplined and at times opportunistic—imposed order in a fractured State. The first decades were marked by struggles between competing factions, from the rivalry between Simón Bolívar and José Antonio Páez to later military-led conflicts, including the struggles of the Blue Federalists in the 1860s and Cipriano Castro’s rise at the turn of the 20th century. Yet, the military’s rigid hierarchy and capacity for decisive action secured its position as the nation’s dominant force. Soldiers dictated national policies and shaped Venezuela’s fate from barracks and battlefields, not from parliamentary halls. Civilian governance, fragmented and short-lived, repeatedly failed to unify the country amid ongoing strife.

3

This legacy endures in General en Jefe Vladimir Padrino López and General en Jefe Diosdado Cabello, who embody the military’s entrenched presence in Venezuela’s political structure. Padrino López, as Minister of Defense, represents the continuity of military influence within the State. His strategic alliance with Nicolás Maduro, grounded in unwavering loyalty and ideological alignment with Hugo Chávez’s Bolivarian revolution, cements his role as a linchpin of the regime’s survival. Diosdado Cabello, who straddles both military and civilian power, leverages his military background to reinforce the government’s authority. Together, they embody the enduring fusion of discipline, ambition, and coercive power.

4

Vladimir Padrino López is widely regarded as a highly disciplined and pragmatic individual. He combines the traits of a loyal military officer with the political acumen necessary to navigate Venezuela’s volatile political landscape. He presents himself as a defender of institutional order and frequently emphasizes the military’s role as a stabilizing force in Venezuela. However, beneath this outward professionalism lies a figure integral to the Maduro regime’s political survival. Padrino López’s loyalty to Maduro has been central to the regime’s endurance. His calculated diplomacy, unlike the confrontational style of other officials, positions him as a pragmatic actor, particularly in dealing with international actors. He balances his public military role with behind-the-scenes influence and leverages his position to navigate internal power struggles. His emphasis on anti-imperialism and nationalism solidifies his standing within the military and political elite.

5

Padrino’s alleged role in the regime’s repression has made him controversial. He has been accused of involvement in systemic military corruption and illicit activities, including drug trafficking and illegal mining. These allegations raise concerns about his complicity in the regime’s criminal activities. His actions reflect calculated pragmatism: he presents himself as a pillar of stability, yet his actual influence remains ambiguous. Some analysts suggest that he could emerge as a power broker in times of crisis.

6

As we analyze the present power structures and their ties to Chávez’s legacy, we must examine the broader historical forces at play. Though often regarded as the architect of Venezuela’s autocratic system, Chávez both emerged from and reinforced the country’s longstanding traditions of militarism and populism. His rise was not an isolated event but the culmination of nearly two centuries of political and social currents. To focus solely on him is to overlook the historical forces that enabled and shaped his rule. Understanding Venezuela’s path to autocracy requires recognizing its political evolution—see Appendix: Constitutional Evolution in the 19th to 20th Centuries.

~

*

Chapter XI

*

The Third Sign

~

The Asymmetry of Political Parties

1

Since the late 20th century, Venezuela’s political landscape has undergone significant transformation, driven by persistent socio-economic instability that disproportionately affected the middle and lower classes. The democratic system established in 1958 was initially defined by a two-party duopoly—Acción Democrática (AD) and Partido Social Cristiano (COPEI)—instituted under the Pacto de Punto Fijo to stabilize democratic governance through alternating power-sharing (see item 26—Constitution of 1961—Appendix, A-1). [1][2][3] Over time, however, this duopoly increasingly monopolized the political arena and marginalized other voices, especially those of socialist and leftist groups. This exclusion not only suppressed pluralistic participation but also deepened discontent among Venezuela’s disadvantaged populations—a factor that ultimately contributed to the system’s collapse. [4]

2

Economic mismanagement, inequality, and political corruption during the 1980s and 1990s further discredited the two-party system. A widening debt crisis, coupled with falling oil prices, exacerbated social inequalities.[5][6] The Caracazo riots of 1989 marked a decisive rupture by exposing the growing gulf between the ruling elite and the general population and signaling the end of the old political order. [7] These riots, which erupted in response to austerity measures imposed by the International Monetary Fund, revealed deep political and social fractures in Venezuelan society. [8]

3

In the aftermath of these systemic failures and societal fractures, Hugo Chávez’s Movimiento V República (MVR) emerged in 1999 as a dominant force, offering populist rhetoric and pledges of wealth redistribution fueled by oil revenues. The Movimiento V República eventually transformed into the Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela (PSUV) in 2007. This transition not only solidified the political left’s dominance but also reduced internal factionalism that could more effectively enforce its policies. [9][10][11]

4

Chávez’s death in 2013 left a power vacuum, and Nicolás Maduro’s rise to power was contested within the Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela. Factionalism, particularly between military and civilian wings, complicated governance. Maduro’s consolidation of power relied on autocratic legalism—a practice involving the manipulation of the constitution, judicial subversion, and the exploitation of elections to sustain a democratic façade. Extralegal tactics, however, (such as repression, media censorship, and the co-optation of all branches of government) became essential means by which the regime maintained control. [12] [13][14]

5

Though new opposition parties emerged, the Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela continued to dominate the political landscape. Fragmentation became a defining obstacle for opposition parties, with internal disagreements over strategy and competing visions for engagement with the regime. The Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela‘s strategy for weakening opposition parties persisted through judicial and electoral manipulation and the promotion of splinter groups, which led to a continued weakening of democratic resistance.

6

The opposition parties struggled to present a united front: a vulnerability that both Chávez and Maduro’s governments actively exploited. This partly explains the opposition’s failure in presenting itself as an effective alternative. Pivotal moments in Venezuela’s political crises were the 2004 recall referendum (when Chávez narrowly survived his recall) and the Ruling 156 by the Tribunal Supremo de Justicia in 2017 (which stripped the opposition-controlled Asamblea Nacional of its powers)—events that further deepened political tensions. [15] [16][17]

7

As the political landscape became increasingly fragmented, opposition leaders attempted to develop alternative strategies, and new opposition parties emerged. Altogether, at one point, there were 49 parties (see Appendix: Item B). Despite this expansion, the ruling party has maintained its dominance, while the opposition is still in disarray. Political splintering has become a defining barrier for the opposition in mounting a challenge against the Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela and has led to repeated failures in electoral and non-electoral arenas: internal divisions over strategy mean that some factions advocate dialogue while others push for more confrontational approaches. The Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela has played a role through its policy of “divide and rule.” By co-opting certain opposition leaders, creating splinter groups, and using judicial and electoral mechanisms to weaken opposition parties, the regime has effectively neutralized potential threats to its dominance.

~

Endnotes—Chapter XI

- [1] Martz, John D., Acción Democrática. Evolution of a Modern Political Party in Venezuela, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1966). Provides a detailed history of the Democratic Action (AD) party in a PhD thesis on Venezuela. https://doi.org/10.1215/00182168-46.4.468 .

- [2] Ellner, Steve, “Venezuelan Revisionist Political History, 1908-1958: New Motives and Criteria for Analyzing the Past” (Latin American ResearchReview: The Latin American Studies Association, 30, no. 2, 1995), 91-121. This article offers critical context for the history of the Social Christian COPEI Party. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2503835 .

- [3] Handlin, Samuel Paltiel, “The Politics of Polarization: Legitimacy Crises, Left Political Mobilization, and Party System Divergence in South America” (PhD diss., Political Science: University of California, Berkeley, Fall 2011), 8, 39-48, 54, 59, 73, 79, 81-86, 91-93, 95, 116, 168, 172.

- [4] Myers, David J. “The Struggle to Legitimate Political Regimes in Venezuela: From Pérez Jiménez to Maduro” (Latin American Research Review: Cambridge University Press, October 23, 2017). DOI: https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.240 .

- [5] Kornblith, Miriam and Levine, Daniel H. “Venezuela: The Life And Times Of The Party System,” Kellogg Institute for International Studies, University of Notre Dame , Working Paper no. 197, June 1993). https://pdba.georgetown.edu/Parties/Venezuela/Leyes/PartySystem.pdf.

- [6] Corrales, Javier, Fixing Democracy: The Venezuela Crisis and Global Lessons (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021), 99-133.

- [7] López Maya, Margarita “The Venezuelan Caracazo of 1989: Popular Protest and Institutional Weakness,” Journal of Latin American Studies, 2003), 35, 117–137. DOI: 10.1017/S0022216X02006673

- [8] Naím, Moises, Paper Tigers and Minotaurs: The Politics of Venezuela’s Economic Reforms, (Washington: The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace 1993). https://observationsonthenatureofperception.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/4d0d0-papertigersandminotaurs.pdf.

- [9] “Dossier No. 61: The Strategic Revolutionary Thought and Legacy of Hugo Chávez Ten Years After His Death,” (Monthly Review Online, Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, March 1, 2023). https://mronline.org/2023/03/01/dossier-no-61-the-strategic-revolutionary-thought-and-legacy-of-hugo-chavez-ten-years-after-his-death/ .

- [10] Marta Harnecker, Understanding the Venezuelan Revolution: Hugo Chávez Talks to Marta Harnecker (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2005), 45-7.

- [11] Barry Cannon, Hugo Chávez and the Bolivarian Revolution: Populism and Democracy in a Globalised Age (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2009), 101-3.

- [12] Gregory Wilpert, Changing Venezuela by Taking Power: The History and Policies of the Chávez Government (London: Verso Books, 2007), 102-04.

- [13] Javier Corrales, and MIchael Penfold, Dragon in the Tropics: Hugo Chávez and the Political Economy of Revolution in Venezuela (Washington: Brookings Institution Press, 2011), 19-24, 30-34.

- [14] Tiago Rogero, “Evidence shows Venezuela’s election was stolen—but will Maduro budge?” (The Guardian, August 6, 2024). https://www.theguardian.com/world/article/2024/aug/06/venezuela-election-maduro-analysis.

- [15] Gustavo Delfino and Guillermo Salas, “Analysis of the 2004 Venezuela Referendum: The Official Results Versus the Petition Signatures,” (Project Euclid, November 2011). DOI: 10.1214/08-STS263

- [16] Rafael Romo, “Venezuela’s high court dissolves National Assembly” (CNN, March 30, 2017. https://www.cnn.com/2017/03/30/americas/venezuela-dissolves-national-assembly/index.html.

- [17] Margarita López Maya, “Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez: Savior or Danger?” (Latin American Perspectives, vol. 29, no. 6, 2002), 88-103—provides critical context to the 2004 Recall Referendum. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2692130