Ricardo F. Morín

October 2025

Oakland Park, Fl

Introduction

Perception often seems immediate and uncomplicated. We see, we hear, we react. Yet between that first contact with the world and the choices we make in response, something slower and more fragile takes place: the formation of meaning. In that interval—between what appears and what we assert—not only understanding is at stake, but ethics as well.

This essay begins with a simple question: what changes when understanding matters more than assertion? In a culture that prioritizes reaction, utility, and certainty, pausing to perceive can seem inefficient. Yet it is precisely this pause that allows experience to take shape without force and keeps the relationship between consciousness and the shared world in proportion.

The Ethics of Perception does not propose rules or moral systems. It examines how sustained attention—able to receive before imposing—can restore coherence between inner life and external reality. From this basic gesture, ethics ceases to operate as an external norm and becomes a way of being in relation.

Perception

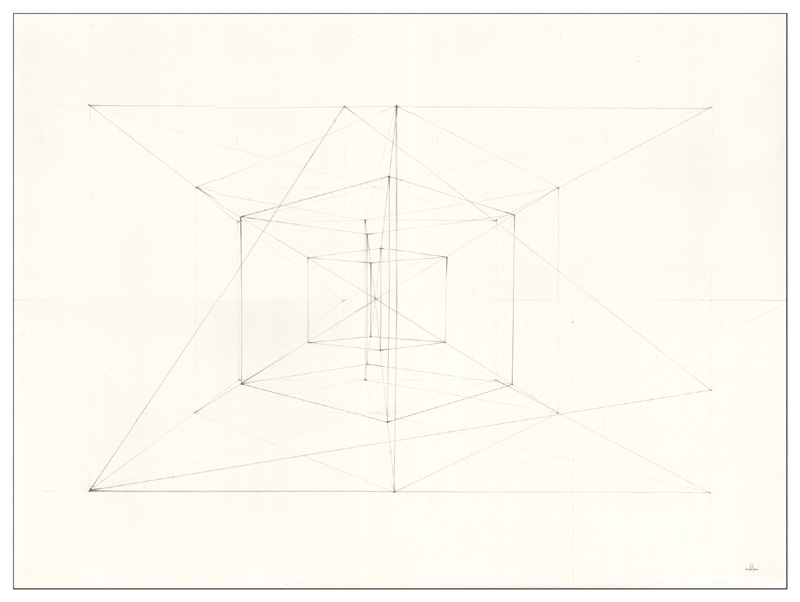

Perception may be understood as the emergent outcome of mechanisms collectively designated as intelligence in the abstract. These mechanisms do not operate solely as interior cognitive functions, nor are they reducible to external systems, conventions, or instruments. Perception arises at the continuous interface between interior awareness and exterior structure, where sensory intake, pattern recognition, and interpretive ordering converge through sustained attunement.

Such a relation does not presume opposition between internal and external domains. Cognitive processes and environmental conditions function as co-present and mutually generative forces. Disruptions frequently described as pathological more accurately reflect misalignment within this reciprocal relation rather than intrinsic deficiency in any constituent mechanism. When normative frameworks privilege particular modes of perceptual attunement, divergence is reclassified as deviation and difference is rendered as dysfunction.

Models grounded in categorization or spectral positioning provide descriptive utility but often presuppose hierarchical centers. An account oriented toward attunement redirects emphasis away from comparative placement and toward relational orientation. Perceptual coherence depends less on position within a classificatory schema than on sensitivity to the ongoing exchange between interior processing and exterior configuration.

Claims of authority over perceptual normality weaken under recognition of ubiquity. If the interaction between cognitive mechanism and environmental structure constitutes a universal condition rather than an exceptional trait, no institution, metric, or discipline retains exclusive legitimacy to define deviation. Evaluation becomes contextual, norms provisional, and classification descriptive rather than prescriptive.

Within this framework, perception is not measured by conformity, efficiency, or accommodation to dominant systems. Perception denotes the sustained capacity to remain aligned with the dynamic interaction of interior awareness and exterior articulation without collapsing one domain into the other. Such an understanding accommodates analytical abstraction, scientific modeling, artistic discernment, contemplative depth, and systemic reasoning without elevating any singular mode of intelligence above others.

Considered in this light, perception resists enclosure within diagnostic, cultural, or hierarchical boundaries. What persists is not a ranked spectrum of cognitive worth but a field of relational variance governed by emergence, attunement, and reciprocal presence.

1

Understanding begins with seeing the world as it is, before any claim or assertion shapes its meaning. My disposition turns toward perceiving, attending, and responding rather than toward struggle or untested impulse. This orientation works as a discipline through which clarity and proportion take form. Thought, in this sense, does not impose significance; it receives it through the living exchange of experience. Perceiving gathers the immediate presence of the world, and understanding shapes that presence into sense. Both arise from the same motion of awareness, where observation ripens into comprehension. Philosophy then ceases to be an act of mastery and becomes a way of seeing that restores balance between mind and existence.

2

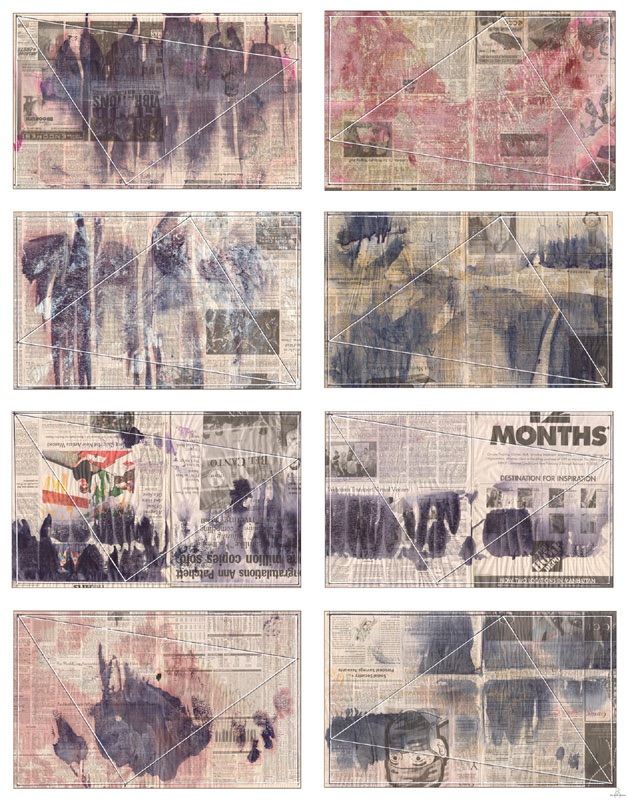

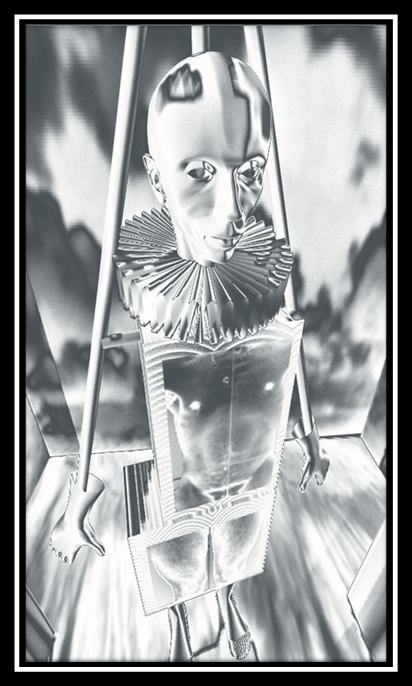

Philosophy has long been driven by the impulse to assert rather than to understand. From antiquity to modern times, thinkers built systems meant to secure certainty and protect thought from doubt. Nietzsche inherited that impulse and inverted it by turning volition into affirmation. His view freed reason from dogma yet confined it within self-assertion. Understanding, by contrast, grows from recognizing that meaning arises in relation. The act of grasping does not depend on force but on perception. When thought observes instead of imposing, the world reveals its own coherence. Ethics springs from that revelation, because to understand is already to enter into relation with what is seen. Comprehension is therefore not passive; it is active participation in the unfolding of reality.

3

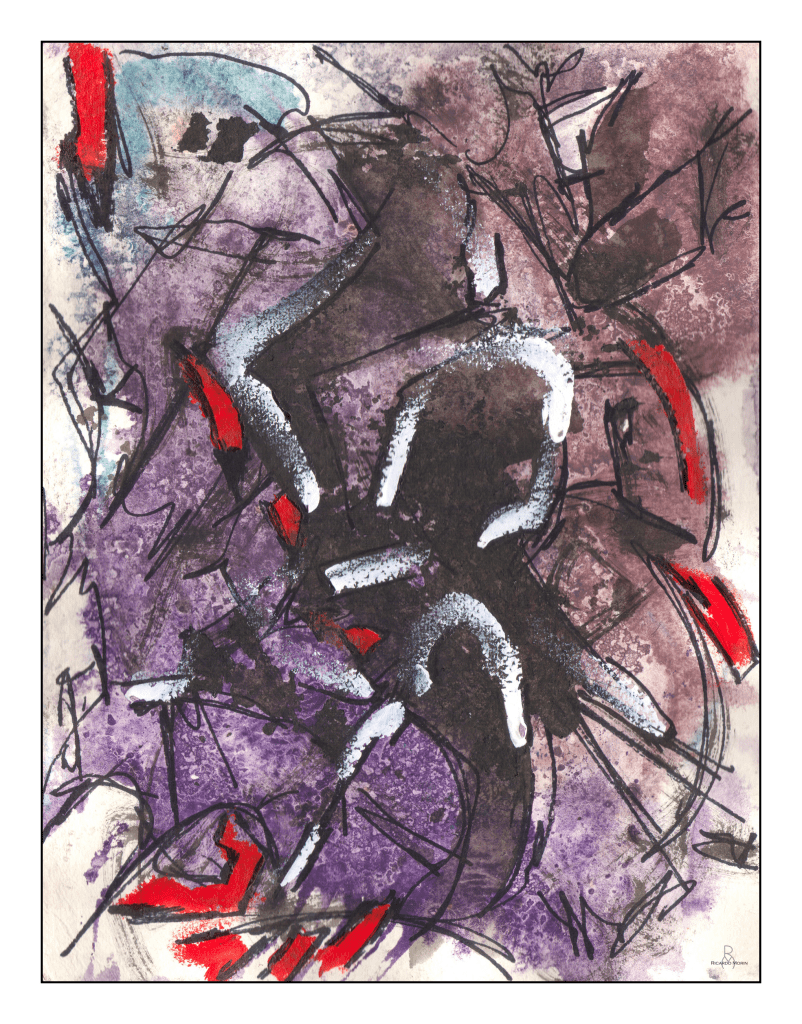

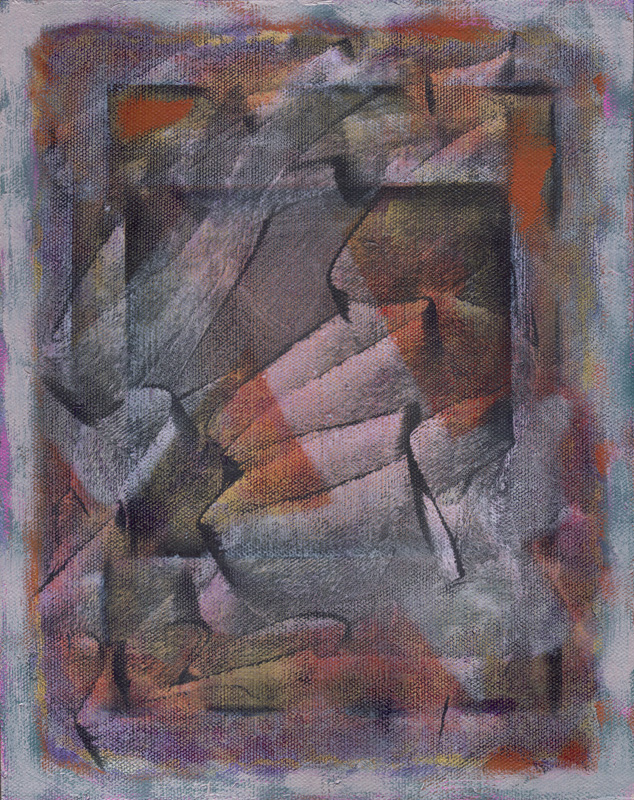

Perception becomes ethical when it recognizes that every act of seeing carries responsibility. To perceive is to acknowledge what stands before us—not as an object to be mastered but as a presence that coexists with our own. Awareness is never neutral; it bears the weight of how we attend, interpret, and respond. When perception remains steady, recognition deepens into connection. A single moment makes this visible: watching an elderly person struggle with opening a door, the mind perceives first, then understands, and then responds—not out of impulse, but out of the recognition of a shared human condition. Art enacts this same movement. The painter, the writer, and the musician do not invent the world; they meet it through form. Each creative gesture records a dialogue between inner and outer experience, where understanding becomes recognition of relation. The moral value of art lies not in a message but in the quality of attention it sustains. To live perceptively is to practice restraint and openness together: restraint keeps volition from overpowering what is seen, and openness lets the world speak through its details. In that steady practice, ethics ceases to be rule and becomes a way of living attentively within relation.

4

Modern life tempts the mind to react before it perceives. The speed of information, the immediacy of communication, and the constant surge of stimuli fragment awareness. In that climate, unexamined volition regains its force; it asserts, selects, and consumes out of bias rather than understanding. What vanishes is the interval between experience and reflection—the pause in which perception matures into thought. Ethical life, understood as living with awareness of relation, re-emerges when that interval is restored. A culture that values perception above reaction can recover the sense of proportion that technology and ideology often distort. The task is not to reject innovation but to exercise discernment within it. Every act of attention becomes resistance to distraction, and every moment of silence reclaims the depth that noise obscures. When perception reaches the point of recognizing another consciousness as equal in its claim to reality, understanding acquires moral weight. Such recognition requires patience—the willingness to see without appropriation and to remain present without possession.

5

All philosophy begins as a gesture toward harmony. The mind seeks to know its bond with the world yet often confuses harmony with control. When understanding replaces conquest, thought rediscovers its natural proportion. The world is not a stage for self-assertion but a field of correspondence where awareness meets what it perceives. To think ethically is to think in relation. The act of grasping restores continuity between inner and outer life and shows that knowing itself is participation. Each meeting with reality—each moment of seeing, listening, or remembering—becomes an occasion to act with measure. The reflective mind neither retreats from the world nor dominates it. It stands within experience as both witness and participant, and lets perception reach its human fullness: the ability to recognize what lies beyond oneself and to respond without domination. When thought arises from attention instead of struggle, it reconciles intelligence with presence and restores the quiet balance that modern life has displaced. In that reconciliation, philosophy fulfills its oldest task—to bring awareness into harmony with existence.