*

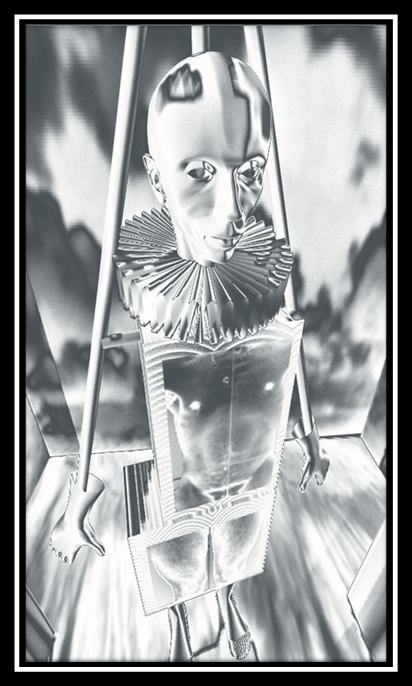

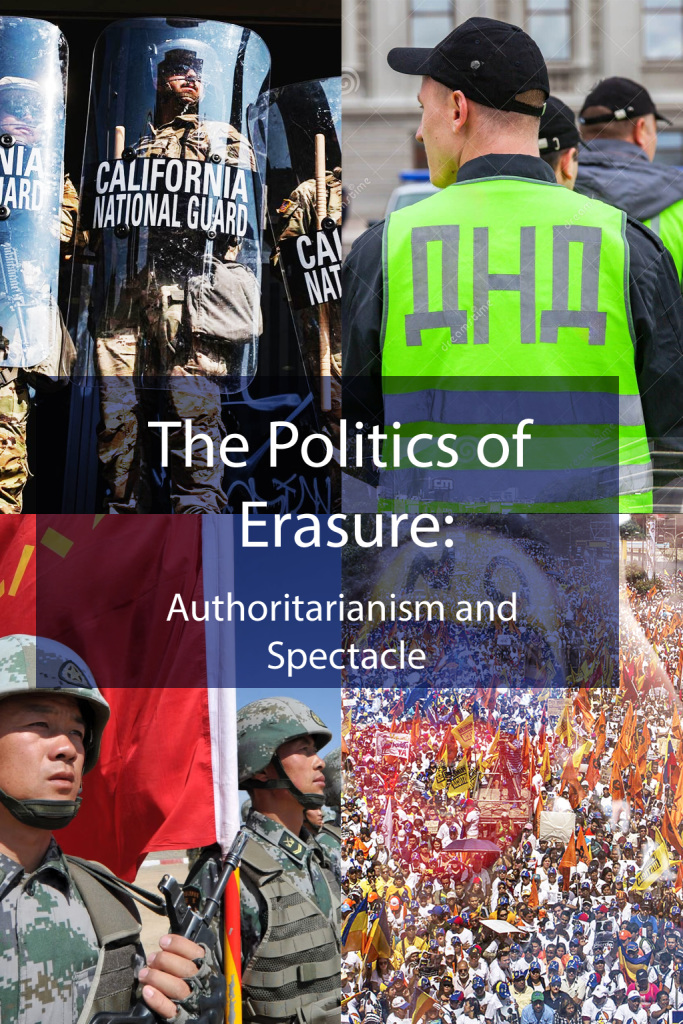

Cover design for the essay “The Politics of Erasure: Authoritarianism and Spectacle.” The composite image juxtaposes surveillance, militarization, propaganda, and mass spectacle to underscore how authoritarian regimes render lives expendable while legitimizing control through display.

By Ricardo Morín, In Transit to and from NJ, August 22, 2025

Authoritarianism in the present era does not present itself with uniform symbols. It emerges within democracies and one-party states alike, in countries with declining economies and in those boasting rapid growth. What unites these varied contexts is not the formal shape of government but the way power acts upon individuals: autonomy is curtailed, dignity denied, and dissent reclassified as threat. Control is maintained not only through coercion but also through the appropriation of universal values—peace, tolerance, harmony, security—emptied of their content and redeployed as instruments of supression. The result is a politics in which human beings are treated as expendable and spectacle serves as both distraction and justification.

In the United States, the Bill of Rights secures liberties, yet their practical force is weakened by structural inequality and concentrated control over communication. After the attacks of September 11, the USA PATRIOT Act authorized sweeping surveillance in the name of defending freedom, normalizing the monitoring of private communications (ACLU 2021). Protest movements such as the Black Lives Matter demonstrations of 2020 filled the streets, but their urgency was absorbed into the circuits of media coverage, partisan argument, and corporate monetization (New York Times 2020). What begins as protest often concludes as spectacle: filmed, replayed, and reframed until the original message is displaced by distractions. Meanwhile, the opioid epidemic, mass homelessness, and medical bankruptcy reveal how millions of lives are tolerated as expendable (CDC 2022). Their suffering is acknowledged in statistics but rarely addressed in policy, treated as collateral to an order that prizes visibility over remedy.

Venezuela offers a more direct case. The Ley contra el Odio (“Law against Hatred”), passed in 2017 by a constituent assembly lacking democratic legitimacy, was presented as a measure to protect tolerance and peace. In practice, it has been used to prosecute journalists, students, and citizens for expressions that in a democratic society would fall squarely within the realm of debate (Amnesty International 2019). More recently, the creation of the Consejo Nacional de Ciberseguridad has extended this logic to place fear and self-censorship among neighbors and colleagues (Transparencia Venezuela 2023). At the same time, deprivation functions as a tool of discipline: access to food and medicine is selectively distributed to turn scarcity into a means of control (Human Rights Watch 2021). The state’s televised rallies and plebiscites portray unity and loyalty, but the reality is a society fractured by exile, with over seven million citizens abroad and those who remain bound by necessity rather than consent (UNHCR 2023).

Russia combines repression with patriotic theater. The 2002 Law on Combating Extremist Activity and the 2012 “foreign agents” statute have systematically dismantled independent journalism and civil society (Human Rights Watch 2017), while the 2022 law against “discrediting the armed forces” criminalized even the description of war as war (BBC 2022). Citizens have been detained for carrying blank signs, which demonstrates how any act, however symbolic, can be punished if interpreted as dissent (Amnesty International 2022). The war in Ukraine has revealed the human cost of this system: conscripts drawn disproportionately from poorer regions and minority populations are sent to the frontlines, their lives consumed for national projection. At home, state television ridicules dissent as treason or foreign manipulation, while parades, commemorations, and managed elections transform coercion into duty. The official promise of security and unity is sustained not by coexistence but by the systematic silencing of plural voices, enforced equally through law, propaganda, and ritual display.

China illustrates the most technologically integrated model. The 2017 Cybersecurity Law and the 2021 Data Security Law require companies and individuals to submit to state control over digital information and extend surveillance across every layer of society (Creemers 2017; Kuo 2021). Social media platforms compel group administrators to monitor content and disperses the responsibility of conformity to citizens themselves (Freedom House 2022). At the same time, spectacle saturates the landscape: the Singles’ Day shopping festival in November generates billions in sales, broadcast as proof of prosperity and cohesion, while state media showcases technological triumphs as national achievements (Economist 2021). Entire communities, particularly in Xinjiang, are declared targets of re-education and surveillance. Mosques are closed, languages restricted, and traditions suppressed—all in the name of harmony (Amnesty International 2021). Stability is invoked, but the reality is the systematic denial of dignity: identity reduced to an administrative category, cultural life dismantled at will, and existence itself rendered conditional upon conformity to the designs of state power.

Taken together, these cases reveal a common logic. The United States commodifies dissent and normalizes abandonment as a permanent condition of public life. Venezuela uses deprivation to enforce discipline and the resulting compliance is publicly presented as loyalty to the state. Russia demands sacrifice and transforms coercion into patriotic duty. China fuses surveillance and prosperity and engineers conformity. Entire communities are suppressed in the name of harmony. The registers differ—commercial, ritualistic, militarized, digital—but the pattern is shared: dissent is stripped of legitimacy, lives are treated as expendable, and universal values are inverted to justify coercion.

References

- ACLU: “Surveillance under the USA PATRIOT Act”. New York: American Civil Liberties Union, 2021. (This article documents how post-9/11 legislation expanded state surveillance in the United States and framed “security” as a justification for reducing privacy rights.)

- Amnesty International: “Venezuela: Hunger for Justice. London: Amnesty International”, 2019. (Amnesty International reports on how Venezuela’s Ley contra el Odio has been used to prosecute citizens and silence dissent under the rhetoric of tolerance.)

- Amnesty International: “Like We Were Enemies in a War: China’s Mass Internment, Torture and Persecution of Muslims in Xinjiang”. London: Amnesty International. 2021. (Amnesty International provides evidence of mass detention, surveillance, and cultural repression in Xinjiang carried out in the name of “harmony” and stability.)

- Amnesty International: “Russia: Arrests for Anti-War Protests”. London: Amnesty International, 2022. (Amnesty International details the systematic arrest of Russian citizens, including those holding blank signs, under laws claiming to protect peace and order.)

- BBC: “Russia Passes Law to Jail People Who Spread ‘Fake’ Information about Ukraine War.” March 4, 2022. (News coverage of Russia’s 2022 law criminalizing criticism of the war shows how “discrediting the armed forces” became a punishable offense.)

- CDC.: “Opioid Overdose Deaths in the United States. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention”. 2022. (The CDC provides statistical evidence of widespread loss of life in the U.S. and underscores how entire populations are treated as expendable in public health.)

- Creemers, Rogier: “Cybersecurity Law of the People’s Republic of China”: Translation with Annotations. Leiden University, 2017. (An authoritative translation and analysis of China’s 2017 Cybersecurity Law illustrate how digital oversight is institutionalized.)

- UNHCR: “Refugee and Migrant Crisis in Venezuela: Regional Overview”. Geneva: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2023. (This report offers figures on the Venezuelan exodus and highlights the mass displacement caused by deprivation and repression.)